Dr Cameron Hazlehurst was a Junior Research Fellow at Queen’s from 1970-72. Some of the research he carried out at that time, and on subsequent visits, forms part of his new book, A Liberal Chronicle in Peace and War (OUP), which provides an essential source for anyone studying the Liberal government in the years 1911-1915. We asked him to tell us more about his work.

Can you tell us a bit about the work you undertook in College that helped to shape the book?

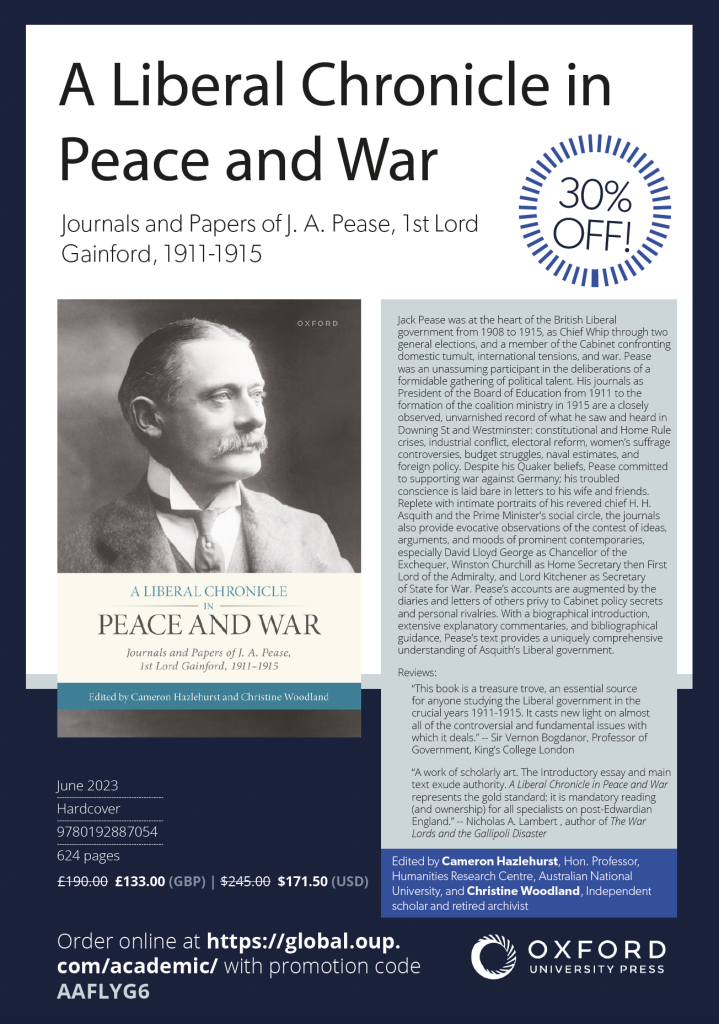

While still a doctoral student at Nuffield College I had discovered the papers of Jack Pease, Chief Whip in the Asquith Liberal government 1908-10, and then a member of the Cabinet until May 1915. While at Queen’s, my collaborator Christine Woodland and I searched for the papers of Pease’s contemporaries with a view to producing a comprehensively annotated edition of the diaries. It became clear that to do justice to the rich veins of source material we found, Pease’s diaries would need to be published in two volumes.

What insights into history can personal accounts provide that official documents do not?

The diaries and letters of participants and observers provide understandings of the cross-currents of opinion, argument, belief, and emotion that lie behind formal submissions and decisions. Departmental files are rich sources of information. But the personal correspondence and musings of ministers and those in their orbit reveal much about which official accounts are silent. A private secretary is privy to the ministerial disagreements that are papered over in the Prime Minister’s Cabinet report to the King. Partners at home in the country receive candid unburdenings about their spouse’s stressful days in Cabinet. Friendly editors record what they learn privately from leading ministers. A General deep in the confidence of the Opposition pens fulminations about what they see and hear in Whitehall….

What are the particular challenges of researching and presenting material of this nature?

The first challenge arises from the recognition that people on the periphery of the highest levels of government often see and hear much that might otherwise be undisclosed. Asquith’s torrent of letters to Venetia Stanley, the young woman whose companionship and affection he craved, are the best known example. But the searches initiated in the Queen’s Back Quad, and sustained over five decades, brought a cornucopia of intimate confessions and commentaries from private secretaries, advisers, friends, families, lovers, and political adversaries.

The biggest challenge, a really great frustration, has been the refusal to this day of access to several collections kept by men who knew Jack Pease well.

The papers exist and we know where they are!

Where did you work when you were at Queen’s in the ‘70s?

In my study writing hundreds of letters enquiring about the possible survival of family papers, and sorting photocopies and transcriptions gathered from the Bodleian, the British Museum Library (it did not become the British Library until 1973), and other repositories. On trains, buses, and taxis en route to libraries, archives, and private homes around the country. There are so many indelible memories of warm hospitality and exciting discoveries: the charred edges of William Wedgwood Benn’s typed diaries, saved from a fire in an outhouse; the meticulously handwritten diaries of the 27th Earl of Crawford and Balcarres read during a weekend as guests at Balcarres House; and many more.

What were your favourite places in Oxford when you were here?

The Sorbonne Restaurant where I would lunch with my closest friend Martin Gilbert with whom I ran a seminar (unrecognised by the History Faculty!) on Sources and Problems in Modern British Political History.

The Casse Croute bistro below La Sorbonne which welcomed small children (my son David, now a senior public servant in the Australian Prime Minister’s Department, was born in 1969).

The Bodleian underground stacks that I was free to roam when I was appointed by the Library as an honorary consultant on modern political papers.

The Worcester College gardens, a serene retreat from the bustle of the town and the intensity of research and writing.