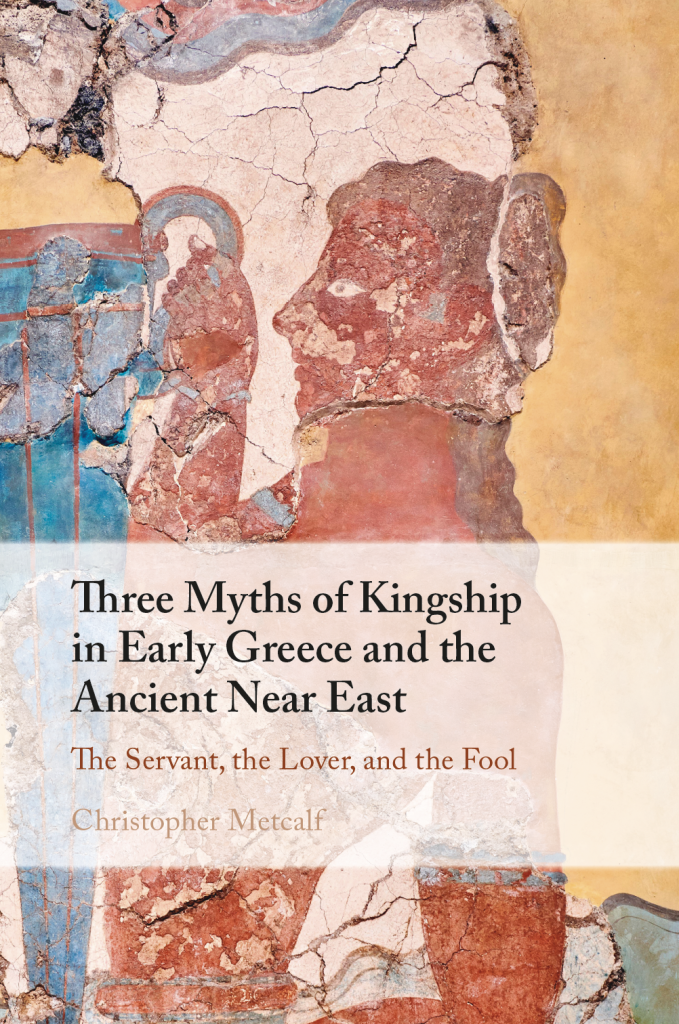

Lobel Fellow in Classics Dr Christopher Metcalf has published Three Myths of Kingship in Early Greece and the Ancient Near East: The Servant, the Lover, and the Fool (Cambridge University Press, 2025). We asked him to tell us more about the new discoveries that have informed his research.

Can you tell us about the recent primary source discoveries that informed your latest book Three Myths of Kingship in Early Greece and the Ancient Near East and how you used them in your research?

The most important new source is a long Sumerian literary text (ca. 2000 BC) in the British Museum, which my colleague Dr Marie-Christine Ludwig and I published in 2017. Back then I didn’t fully grasp the wider significance of the text, which began to dawn on me only in the course of my undergraduate lectures on an early Greek poem (the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite). It is thanks to my period of sabbatical leave (2022-23) that I was finally able to work out the mythical story-pattern (which I call the myth of the Goddess and the Herdsman) that underlies the Sumerian text, and that connects it to an important kingship-myth in early Greece (and later in Rome). More generally it’s important to realise that our knowledge of the ancient world is constantly being enriched by new primary sources – indeed some relevant texts have been published so recently that I wasn’t able to include them in the book.

It’s important to realise that our knowledge of the ancient world is constantly being enriched by new primary sources.

The Myth of the Servant explores the rise of individuals of non-royal lineage to power. How do you think this myth reflects the social or political structures of the time, in terms of the perception of legitimacy and divine right?

It was probably a simple historical fact that, from time to time, a newcomer arrived on the scene and founded a new royal line that was unconnected to existing dynasties. In the ancient perspective such an event could not be left unexplained, and what I tried to show in the book is that ancient myth-makers resorted to a shared underlying story-pattern (which I call the Myth of the Servant) to supply a plausible origin-story for the emergence of the new king.

This story of course reflects the social and political structures of the time, in various ways: in the Mesopotamian setting, for instance, the future king was typically said to have served as a cup-bearer to an existing, usually fictional royal figure, before taking the throne himself. This has to do with the fact that, as documentary evidence shows, cup-bearers were very powerful court officials in the ancient Near East, and it seems that this office did indeed offer an opportunity for advancement to members of non-elite families. But elsewhere this element of the myth was handled differently: early Greek authors seem to have avoided it (unless they were writing specifically about Near Eastern kings), probably because the whole idea of a courtly structure with a cup-bearer had less social and political plausibility in a Greek setting and for a Greek audience, following the disappearance of the Mycenaean palace culture in 1200 BC.

What does the ‘Goddess and the Herdsman’ myth suggest about the role of women in ancient leadership?

Here it is important to note that the woman in question was a goddess (such as the Sumerian Inana or the Greek Aphrodite) – this means that while the female partner had certain characteristics of mortal women, her divine status also made her much more powerful than any ordinary person. The gender dynamics at play here are very complex and interesting, and while I try to outline some ideas in the book I’m sure that much more remains to be said. In particular I’m intrigued by the fact that the final element of the Myth of the Servant often involves winning the hand of a woman (e.g. the new king marries the queen of the existing ruler). In the Sumerian context it’s not impossible to imagine that the goddess Inana (i.e. the same figure who is central to the myth of the Goddess and the Herdsman) was involved in this, but the sources are fragmentary. In a Greek setting one might think of Odysseus’ efforts to regain the hand of Penelope, which is a central part of his quest to reassert his kingship in Ithaca. In the book I wasn’t quite able to work this out: I hope others will do more.

You explain that kings and others often depended on their ability to articulate the divine will. How did kings’ relationships with poets, priests, or prophets shape their rule and the narratives surrounding their authority?

Here the interesting point, to my mind, is that many ancient myths of kingship (such as the Myth of the Servant and the Myth of the Goddess and the Herdsman) quite straightforwardly legitimise the mortal king, and the divine support claimed by the king was an important aspect of that. But there were also other figures – such as poets or prophets – who claimed to be legitimised by the gods, and these figures happened to be the groups who authored most of our ancient texts. I think that this explains why many ancient literary sources that revolve around kings are so critical of mortal rulers – indeed some (such as the Gilgamesh-epic, the Iliad, and others) open very emphatically with disastrous transgressions committed by a kingly figure. Another part of this pattern is that it was usually the common people who bore the negative consequences, not the leaders themselves. Perhaps this shows that such texts were composed and performed with a didactic or admonitory intent, to remind an audience (which may have included royal or aristocratic figures) that the power of the gods remains supreme, and that non-royal experts (such as poets, prophets, etc.) are better than kings at understanding what the gods want.

Has anything surprised you in your research for this book?

The coherence of the mythical story-patterns surprised me to some extent. These days we (as scholars) tend to work on very specialised questions, and we tend to assume that a given phenomenon is unique and special. And it is – but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is not connected to other phenomena in fields that seem at first sight to be unrelated. In this regard I was struck by the impression that it was relatively straightforward to find what seemed to me to be very productive and significant cross-cultural connections, simply by reading and thinking a bit more broadly than usual. The evidence was (and still is) hidden in plain sight.

I was struck by the impression that it was relatively straightforward to find what seemed to me to be very productive and significant cross-cultural connections, simply by reading and thinking a bit more broadly than usual.

What did you enjoy most about this project?

Perhaps the sense that aspects of my research were starting to converge, in an entirely unplanned and fortuitous way, with material that was known to me primarily from my undergraduate teaching. All three chapters of the book reflect this type of convergence. It seems to be a luxury nowadays for an academic to have the time to allow these productive coincidences to happen, and to follow one’s hunches rather than to tick off items of a work programme that has been determined and agreed in advance. So I am extremely grateful for the time and liberty that I have enjoyed in writing this book.

The history of Classics at Queen’s is an interesting one. How do you see your own research continuing this rich tradition?

Mainly I suppose in the sense that Queen’s has traditionally had great breadth in the Humanities, especially in the study of ancient and modern languages, across a wide range of disciplines. Maybe that explains why it feels quite natural here for e.g. a Hellenist to be in dialogue with an Egyptologist or a Sinologist. That approach has no doubt left its mark on the College’s profile in Classics, and if my work in any way helps to continue this tradition then there is for me no greater reward than that.