SIR JOSEPH WILLIAMSON (1633-1701) has a close association with the College as a Fellow and benefactor. His legacy can be seen in the fabric of the buildings as well as his gifts, which have contributed to learning at the College over generations. Physically, it is marked by a statue in a niche outside the Library, by stained glass in the Upper Library and in the Hall, and in a portrait from the studio of Sir Peter Lely, purchased by Provost Joseph Smith in 1751 as a tribute to Williamson.

But even as recently as 2011, the College could mark Williamson’s life and career in an exhibition on the ‘Great Benefactor’ without giving space to his close connection to the establishment of the transatlantic trade in enslaved African people. In the light of recent research, both in the College and elsewhere, this association has become more apparent. The portrait’s temporary rehanging and accompanying exhibition, with the necessary curation and context, now provide us with an opportunity to reconsider Williamson’s legacy and his connection with the Royal African Company, in the hope of achieving a more complete account of the College’s history.

1694 sculpture of Williamson attributed to John Vanderstein.

The Royal African Company and the transatlantic slave trade

The transatlantic slave system, developed by the Dutch and English in the seventeenth century, was marked by its cruelty and its degradation of human lives into a form of capital. By establishing forts and warehouses on the West African coast that were defended by the state, the Royal African Company, a joint stock company, provided a vehicle for thousands to invest in the enslavement and transportation of African people to British colonies in the Caribbean and North America. There enslaved people were forced to labour on plantations and estates, producing tobacco, sugar and, later, cotton for sale in Britain and its colonial markets.

In the later seventeenth century, the restored monarchy of Charles II consciously linked its fortunes and authority to British colonial power. In 1660, after observing the Dutch trade in gold and enslaved Africans during the court’s exile, the Crown established the Company of Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa. By 1663, it had established forts in West Africa from which it shipped enslaved Africans to the Americas. In 1672, following losses made in the First Anglo-Dutch war, the company was refounded as the Royal African Company of England.

Between 1673 and 1711, the Royal African Company sold 90,786 enslaved people, with many more dying in hundreds of voyages across the Atlantic. William III liberalised the Company’s monopoly, providing an opportunity for independent English traders in enslaved people, still on the basis of these state structures. According to recent historical estimates, during the eighteenth century Great Britain shipped 2,545,298 enslaved people, of whom 394,963 died during the crossing.

Williamson and the transatlantic slave trade

Described as a ‘chief minister of state’ by Samuel Pepys, Williamson helped to direct the government’s foreign affairs, in the course of which he built up a powerful intelligence-gathering system, incorporating a network of correspondents and informers at home and overseas. He was an associate of many leading figures of the day, straddling effectively the worlds of the royal court and the City, as well as serving as second President of the Royal Society.

As such, Williamson would have been seen as a useful man to have serve as ‘Assistant’ (i.e. a director) of the Royal African Company. In addition to the financial gain from his shares in the company and the fees received for attending meetings, the social clout of the Company also undoubtedly aided Williamson in his career.

As Under-Secretary and then Secretary of State, Williamson helped to implement policy on West Africa, the Caribbean, and the North American colonies, as well as the broader strategy in relation to the Dutch and Spanish – both competitors in the trade. His role also made him ex officio member of the Lords of Trade and Plantations, which profoundly shaped the transatlantic trade system and colonial governance.

The large correspondence that Williamson meticulously preserved in the State Paper Office also speaks of his sustained involvement in the suppression of resistance by enslaved people. As archival remains, these are powerful reminders of the importance of such uprisings, an echo of the hundreds of thousands of voices that are otherwise lost to us. For example, a letter from 1667 records one such incident at Fort James in the Gambia River, during which the formerly enslaved ‘possessed themselves of the island’. Williamson’s close involvement with the Company in financial and strategic terms means that his links with the trade bear comparison to those of men such as Edward Colston, of whom Williamson was an associate. He played a foundational role in the trade, one that was, in the words of the historian Professor William Pettigrew (Lancaster University), both ‘persistent and profitable’.

Williamson’s wealth

Williamson’s background was modest, but respectable. His personal wealth did not just derive from his investment and involvement in the Royal African Company, but came initially from his College emoluments and then to a far greater extent from his government posts, including his oversight of a lottery and the postal service. He returned his wife’s estates in Ireland and England to profit. His wealth at death is recorded as £18,510 5s, along with his estates.

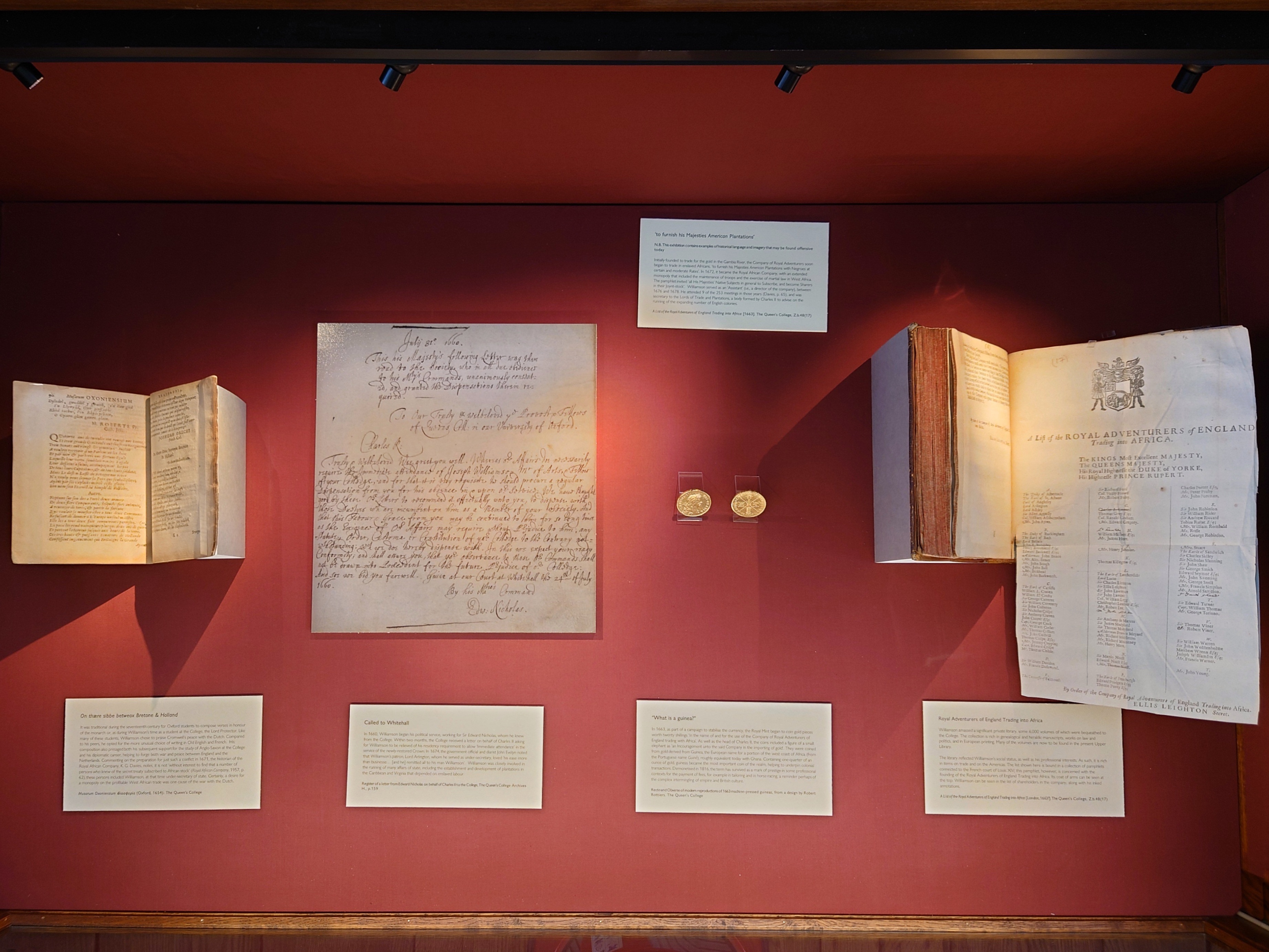

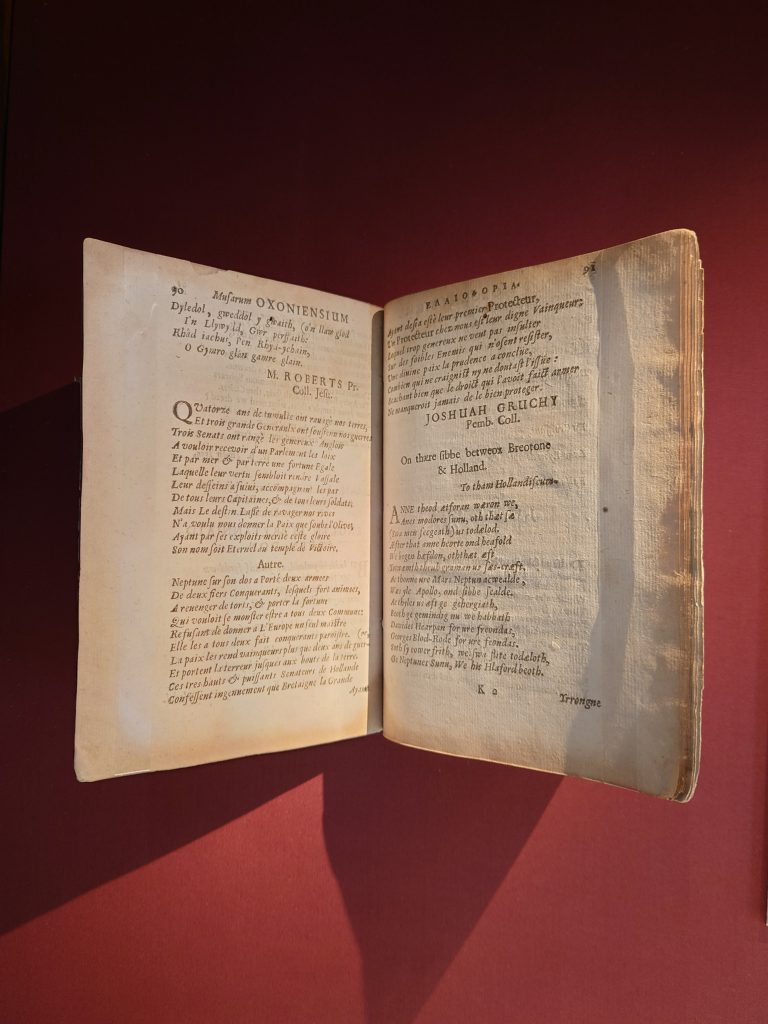

Musarum Oxoniensium ἐλαιοφορία (Oxford, 1654). The Queen’s College

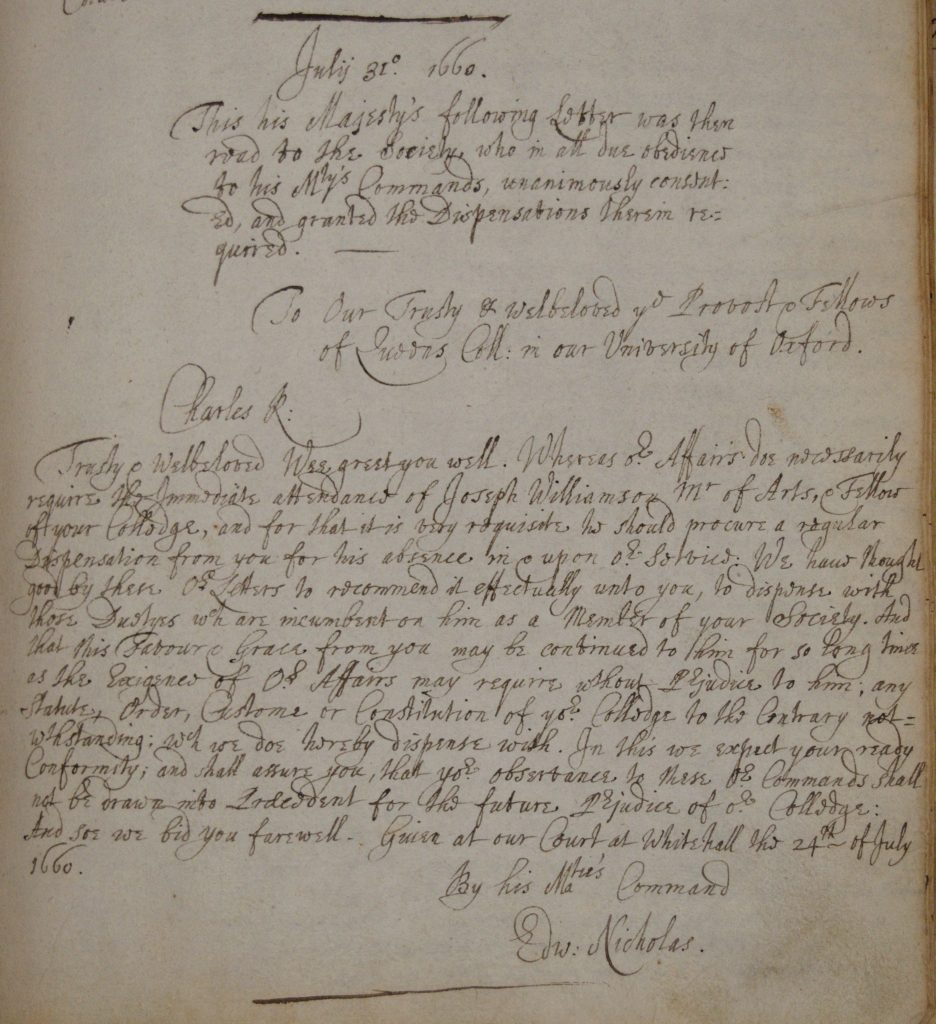

Register of a letter from Edward Nicholas on behalf of Charles II to the College, The Queen’s College Archives H., p.159

Recto and Obverse of modern reproductions of 1663 machine-pressed guineas, from a design by Robert Rottiers. The Queen’s College

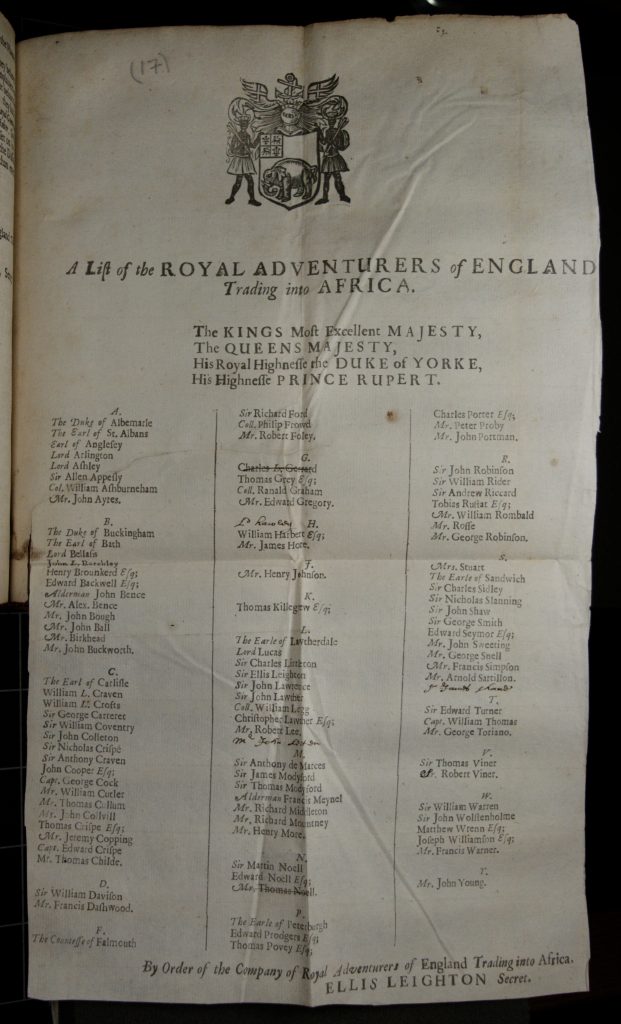

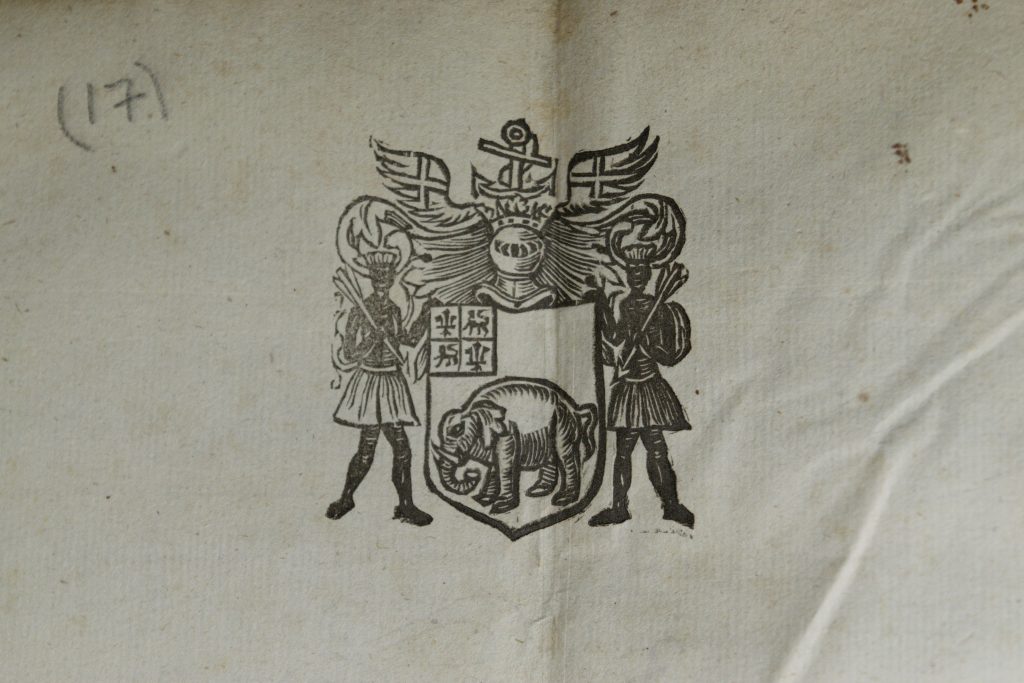

A List of the Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa [1663]. The Queen’s College, Z.b.48(17)

Musarum Oxoniensium ἐλαιοφορία (Oxford, 1654). The Queen’s College

Register of a letter from Edward Nicholas on behalf of Charles II to the College, The Queen’s College Archives H., p.159

Recto and Obverse of modern reproductions of 1663 machine-pressed guineas, from a design by Robert Rottiers. The Queen’s College

A List of the Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa [1663]. The Queen’s College, Z.b.48(17)

On thære sibbe betweox Bretone & Holland

Musarum Oxoniensium ἐλαιοφορία (Oxford, 1654). The Queen’s College

It was traditional during the seventeenth century for Oxford students to compose verses in honour of the monarch or, as during Williamson’s time as a student at the College, the Lord Protector. Like many of these students, Williamson chose to praise Cromwell’s peace with the Dutch. Compared to his peers, he opted for the more unusual choice of writing in Old English and French. His composition also presaged both his subsequent support for the study of Anglo-Saxon at the College and his diplomatic career, helping to forge both war and peace between England and the Netherlands. Commenting on the preparation for just such a conflict in 1671, the historian of the Royal African Company, K. G. Davies, notes, it is not ‘without interest to find that a number of persons who knew of the secret treaty subscribed to African stock’ (Royal African Company, 1957, p. 62); these persons included Williamson, at that time under-secretary of state. Certainly, a desire for a monopoly on the profitable West African trade was one cause of the war with the Dutch.

Called to Whitehall

Register of a letter from Edward Nicholas on behalf of Charles II to the College, The Queen’s College Archives H., p.159

In 1660, Williamson began his political service, working for Sir Edward Nicholas, whom he knew from the College. Within two months, the College received a letter on behalf of Charles II asking for Williamson to be relieved of his residency requirement to allow ‘Immediate attendance’ in the service of the newly-restored Crown. In 1674, the government official and diarist John Evelyn noted that Williamson’s patron, Lord Arlington, whom he served as under-secretary, loved ‘his ease more than businesse… [and he] remitted all to his man Williamson’. Williamson was closely involved in the running of many affairs of state, including the establishment and development of plantations in the Caribbean and Virginia that depended on enslaved labour.

“What is a guinea?”

Recto and Obverse of modern reproductions of 1663 machine-pressed guineas, from a design by Robert Rottiers. The Queen’s College

In 1663, as part of a campaign to stabilise the currency, the Royal Mint began to coin gold pieces worth twenty shillings ‘in the name of and for the use of the Company of Royal Adventurers of England trading with Africa’. As well as the head of Charles II, the coins included a figure of a small elephant as ‘an Incouragement unto the said Company in the importing of gold’. They were coined from gold derived from Guinea, the European name for a portion of the west coast of Africa (from the Portuguese name Guiné), roughly equivalent today with Ghana. Containing one-quarter of an ounce of gold, guineas became the most important coin of the realm, helping to underpin colonial transactions. Demonetised in 1816, the term has survived as a mark of prestige in some professional contexts for the payment of fees, for example in tailoring and in horse racing, a reminder perhaps of the complex intermingling of empire and British culture.

‘to furnish his Majesties American Plantations’

A List of the Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa [1663]. The Queen’s College, Z.b.48(17)

N.B. This exhibition contains examples of historical language and imagery that may be found offensive today

Initially founded to trade for the gold in the Gambia River, the Company of Royal Adventurers soon began to trade in enslaved Africans, ‘to furnish his Majesties American Plantations with Negroes at certain and moderate Rates’. In 1672, it became the Royal African Company, with an extended monopoly that included the maintenance of troops and the exercise of martial law in West Africa. The pamphlet invited ‘all His Majesties’ Native Subjects in general to Subscribe, and become Sharers in their Joynt-stock’. Williamson served as an ‘Assistant’ (i.e., a director of the company), between 1676 and 1678. He attended 9 of the 253 meetings in those years (Davies, p. 65), and was secretary to the Lords of Trade and Plantations, a body formed by Charles II to advise on the running of the expanding number of English colonies.

Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa

A List of the Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa [London, 1663?]. The Queen’s College, Z.b.48(17)

Williamson amassed a significant private library, some 6,000 volumes of which were bequeathed to the College. The collection is rich in genealogical and heraldic manuscripts, works on law and politics, and in European printing. Many of the volumes are now to be found in the present Upper Library.

The library reflected Williamson’s social status, as well as his professional interests. As such, it is rich in items on trade and on the Americas. The list shown here is bound in a collection of pamphlets connected to the French court of Louis XIV; this pamphlet, however, is concerned with the founding of the Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa. Its coat of arms can be seen at the top. Williamson can be seen in the list of shareholders in the company, along with his inked annotations.

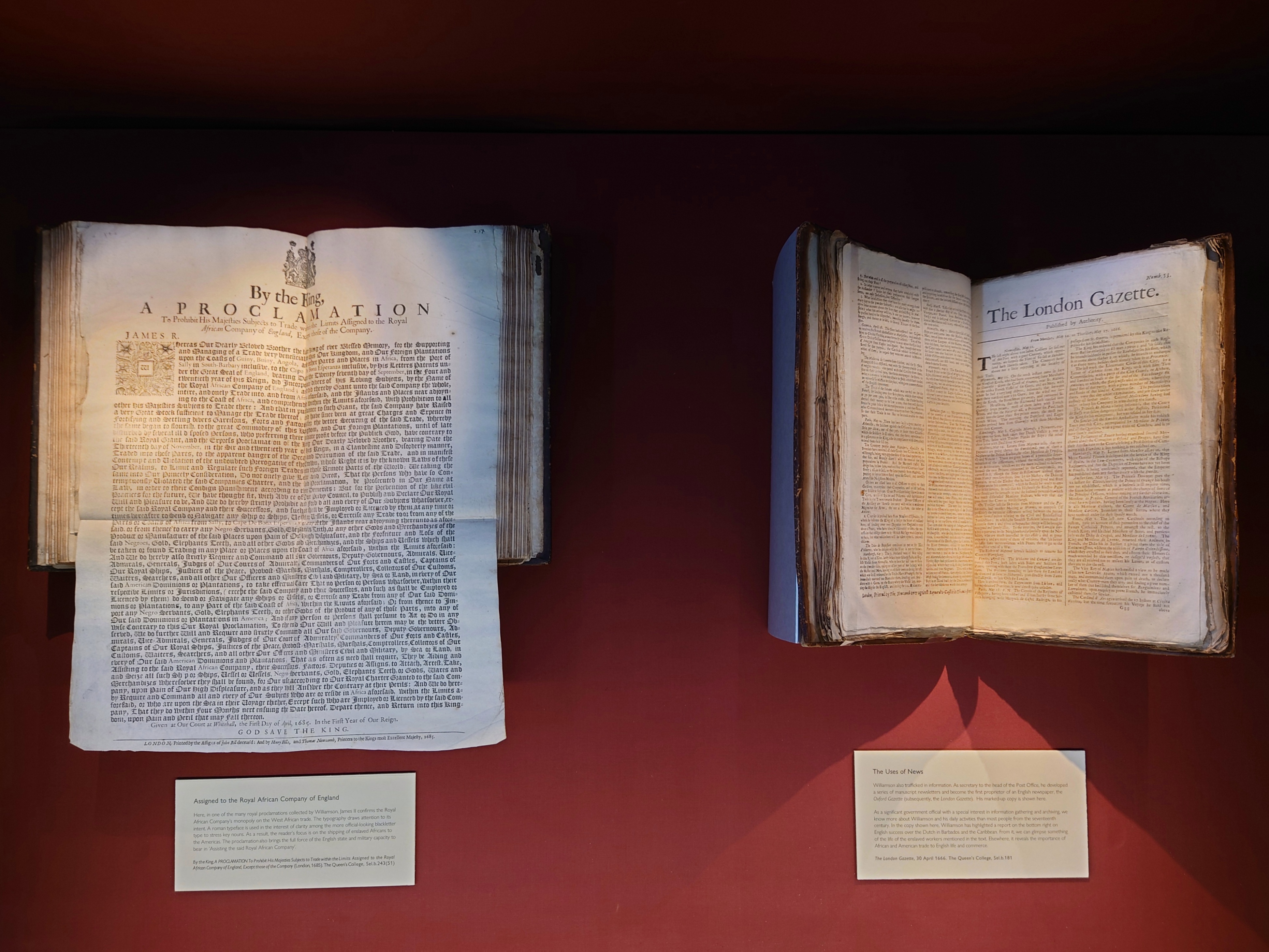

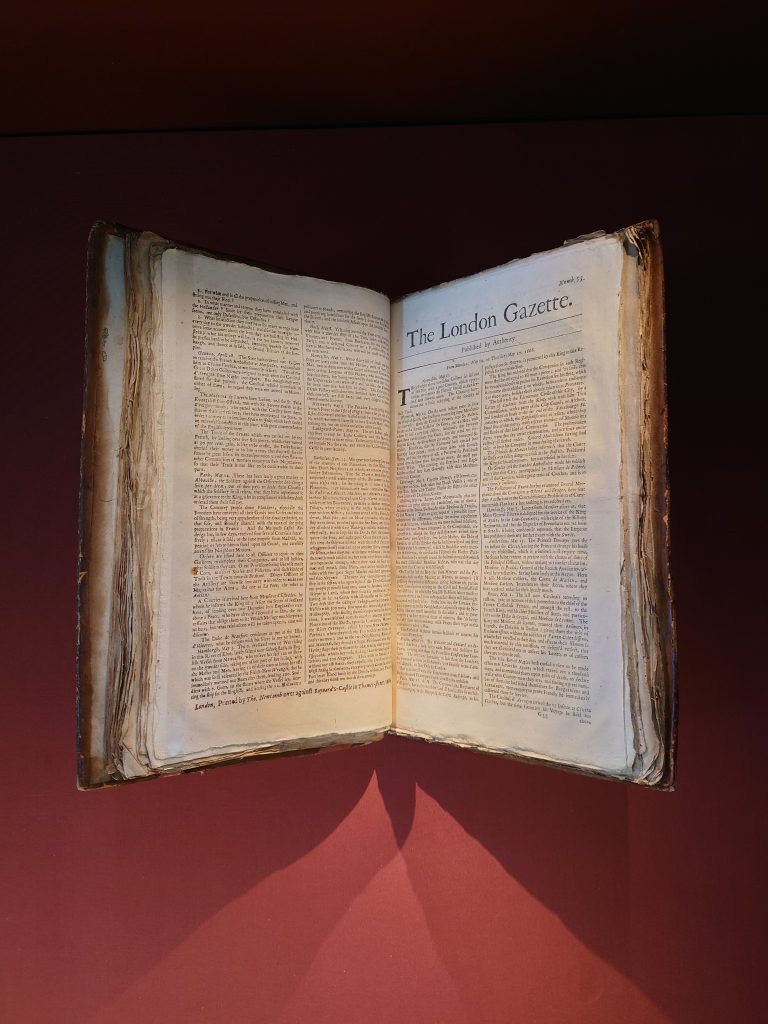

The London Gazette, 30 April 1666. The Queen’s College, Sel.b.181

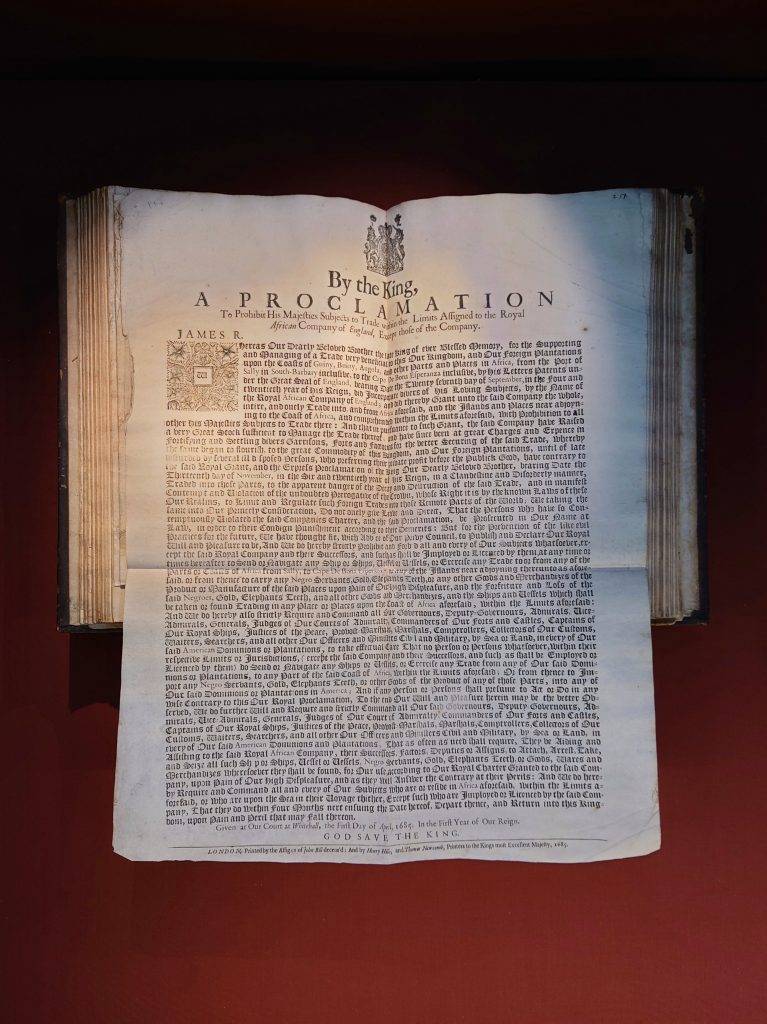

By the King, A PROCLAMATION To Prohibit His Majesties Subjects to Trade within the Limits Assigned to the Royal African Company of England, Except those of the Company (London, 1685). The Queen’s College, Sel.b.243(51)

The London Gazette, 30 April 1666. The Queen’s College, Sel.b.181

By the King, A PROCLAMATION To Prohibit His Majesties Subjects to Trade within the Limits Assigned to the Royal African Company of England, Except those of the Company (London, 1685). The Queen’s College, Sel.b.243(51)

Assigned to the Royal African Company of England

By the King, A PROCLAMATION To Prohibit His Majesties Subjects to Trade within the Limits Assigned to the Royal African Company of England, Except those of the Company (London, 1685). The Queen’s College, Sel.b.243(51)

Here, in one of the many royal proclamations collected by Williamson, James II confirms the Royal African Company’s monopoly on the West African trade. The typography draws attention to its intent. A roman typeface is used in the interest of clarity among the more official-looking blackletter type to stress key nouns. As a result, the reader’s focus is on the shipping of enslaved Africans to the Americas. The proclamation also brings the full force of the English state and military capacity to bear in ‘Assisting the said Royal African Company’.

The Uses of News

The London Gazette, 30 April 1666. The Queen’s College, Sel.b.181

Williamson also trafficked in information. As secretary to the head of the Post Office, he developed a series of manuscript newsletters and become the first proprietor of an English newspaper, the Oxford Gazette (subsequently, the London Gazette). His marked-up copy is shown here.

As a significant government official with a special interest in information gathering and archiving, we know more about Williamson and his daily activities than most people from the seventeenth century. In the copy shown here, Williamson has highlighted a report on the bottom right on English success over the Dutch in Barbados and the Caribbean. From it, we can glimpse something of the life of the enslaved workers mentioned in the text. Elsewhere, it reveals the importance of African and American trade to English life and commerce.

Williamson’s life and career

Born in the Vale of Derwent in Cumberland in 1633 and buried in Westminster Abbey in 1701, Sir Joseph Williamson had a prominent career – a social and political trajectory aided by his time as student and later Fellow at The Queen’s College.

Summoned to government service by the newly-restored Charles II in 1660, he accumulated a lucrative collection of official posts, including Secretary of Foreign Tongues, Keeper of the King’s Library and State Paper Office, Contractor for the Royal Oak Lottery, and editor of the Oxford Gazette, England’s first newspaper. A proven administrator with a particular interest in intelligence networks, he served as Under-Secretary and then Secretary of State for the Southern Department, with responsibilities for West Africa and the American Colonies, and as a member of the Lords of Trade and Plantations.

To these official posts, Williamson also added a range of other activities. He was well known to men such as John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys, and served as President of the Royal Society, which at that time offered a venue for his antiquarian interests. He was also friendly with leading figures in the City of London.

Perhaps as a result of his City connections, Williamson was also recommended to become an ‘Administrator’ to the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa and then its successor, the Royal African Company. His investments in the trade in enslaved Africans include £500 of shares, and his activities as Secretary of State meant that he influenced and helped implement government policy towards the Dutch in relation to the lucrative West African trade, the establishment of slave forts, the protection of slave ships by the Royal Navy, the establishment of the plantation system in Jamaica and Virginia, and the suppression of revolts by enslaved African workers.

In 1679, he married Baroness Clifton, a relation of the king and heir to her brother, the third Duke of Richmond. Although he fell from office as a result of the ‘Popish Plot’ affair, his career had a second act, both as a politician in Ireland and as plenipotentiary and ambassador at the Hague (1697-99). He died without a legitimate heir, and bequeathed his large library along with £6,000 towards the construction of buildings at the College.

Williamson’s gifts to the College

Williamson’s donations to the College are recorded in the Benefactors’ Book. During his lifetime, it lists:

- An inscribed silver trumpet and two banners emblazoned with the College arms

- An inscribed silver basin and water jug

- Twelve forks with inscribed silver handles

- A large silver dish with a matching lid for use by the Provost at High Table

- £1,700 for the construction of the new building in the north-east part of College

In his will, Williamson left:

- £6,000 towards the enlargement or construction of more buildings

- Books from his personal library, as well as the Benefactors’ Book itself

Silver trumpet. The Queen’s College, Oxford.

Sir Peter Lely

The College’s portrait of Williamson is attributed to the studio of Sir Peter Lely (1618 – 80). A Dutch immigrant, he became a freeman of Painter-Stainers’ Company in 1647, and maintained links with exiled royalists at The Hague.

In 1660, Lely became Charles II’s Principal Painter. He produced portraits of many members of the royal court, including the king himself, his consort Catherine of Braganza, and the Duke of York. His patron Anne Hyde, the Duchess of York, also commissioned him to produce the series of portraits – including of Hyde herself – known as The Windsor Beauties (Royal Collection). Lely was also an avid collector of paintings and amassed a large collection of Old Masters, prints and drawings.

Williamson was known for his love of fine clothes – as well as music and dancing – and this can perhaps be seen in the lacework here. His work as Under Secretary might be shown by the paper in his other hand.

Williamson would have attended Lely’s popular studio in Covent Garden, where Lely offered a selection of poses from a book, and painted the faces and hands (although not the latter it seems in this case) to musical accompaniment. The rest was usually completed by assistants. It is unclear how much of this portrait is a studio copy. Williamson presented a later portrait by Godfrey Kneller (1646–1743) to the Royal Society, in which his wealth and status is more prominently on display through his gold brocade. The College’s portrait, perhaps dating from the 1670s, was donated by Provost Joseph Smith (1670–1756).

Sir Joseph Williamson by Peter Lely (studio of). The Queen's College, Oxford.

Sir Joseph Williamson by Godfrey Kneller. The Royal Society.

Sir Joseph Williamson Peter Lely (studio of). Bodleian Libraries.

Curated by Dr. Matthew Shaw, Librarian.