This year marks the 350th anniversary of the Edmond Halley’s joining The Queen’s College as a commoner. This display brings together some of scientist’s works from his career as Clerk of the Royal Society, Astronomer Royal, and Savilian Professor of Geometry.

The items exhibited are also testament to the scientific – and other networks – of the time. At Queen’s, Sir Joseph Williamson, fellow, centre of the government’s spy network, and ‘a great friend to Queen’s Coll. men’ (Anthony Wood) helped to get him to St Helena on a remarkable scientific mission that is a reminder of the ties between science, trade and politics. Despite his youth, Halley’s excellent celestial observational skills, and a series of scientific papers written while a student here at Queen’s forged an entrée into a world that included Robert Hooke, John Flamsteed, Christopher Wren, and Isaac Newton. Halley’s diplomacy and tact were also often called upon to calm the fractious nature of this community. He was well-travelled, a sailor, and delighted in his status as a captain.

Halley’s scientific contributions are significant and varied, ranging from magnetism to the size of atoms, and was based on excellent observation and measurement, the use of historical evidence, and mathematical ability and innovation. For example, he used evidence from Ptolemy’s to show how stars had moved over time, disproving the assumption that stars were fixed. His influence on Isaac Newton and his work on gravitational theory was also profound. Following the publication of Newton’s Principia, Halley’s Synoposis astronomiae cometicae (1705) showed how the exact date of the comet’s return depended on the gravitational interaction between a comet and the planets it passed. Fittingly, he is now remembered for the comet that still bears his name.

Do Look Up!

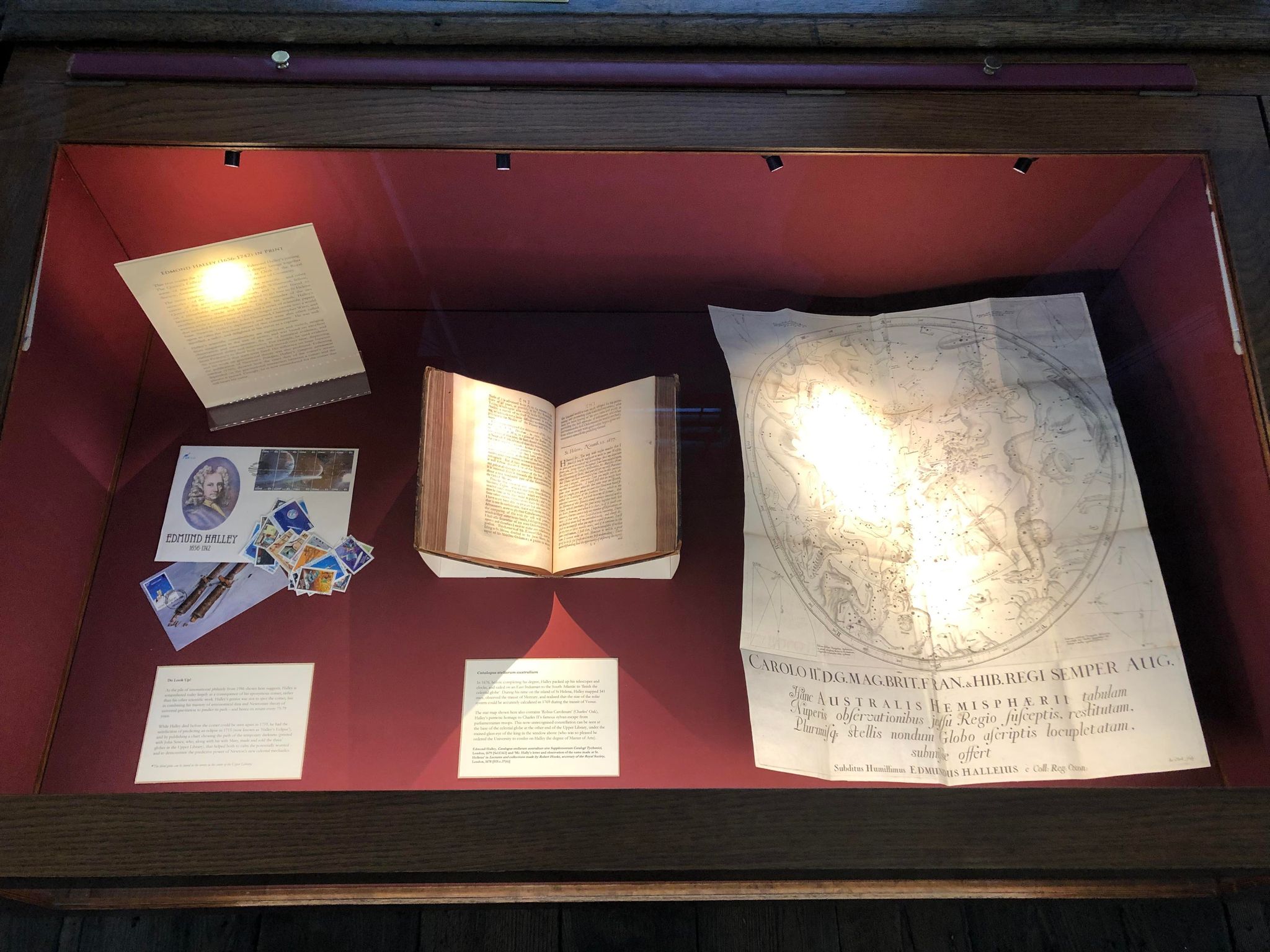

As the pile of international philately from 1986 shown here suggests, Halley is remembered today largely as a consequence of his eponymous comet, rather than his other scientific work. Halley’s genius was not to spot the comet, but in combining his mastery of astronomical data and Newtonian theory of universal gravitation to predict its path – and hence its return every 75-79 years.

While Halley died before the comet could be seen again in 1759, he had the satisfaction of predicting an eclipse in 1715 (now known as ‘Halley’s Eclipse’), and by publishing a chart showing the path of the temporary darkness (printed with John Senex, who, along with his wife Mary, made and sold the three* globes in the Upper Library), that helped both to calm the potentially worried and to demonstrate the predictive power of Newton’s new celestial mechanics.

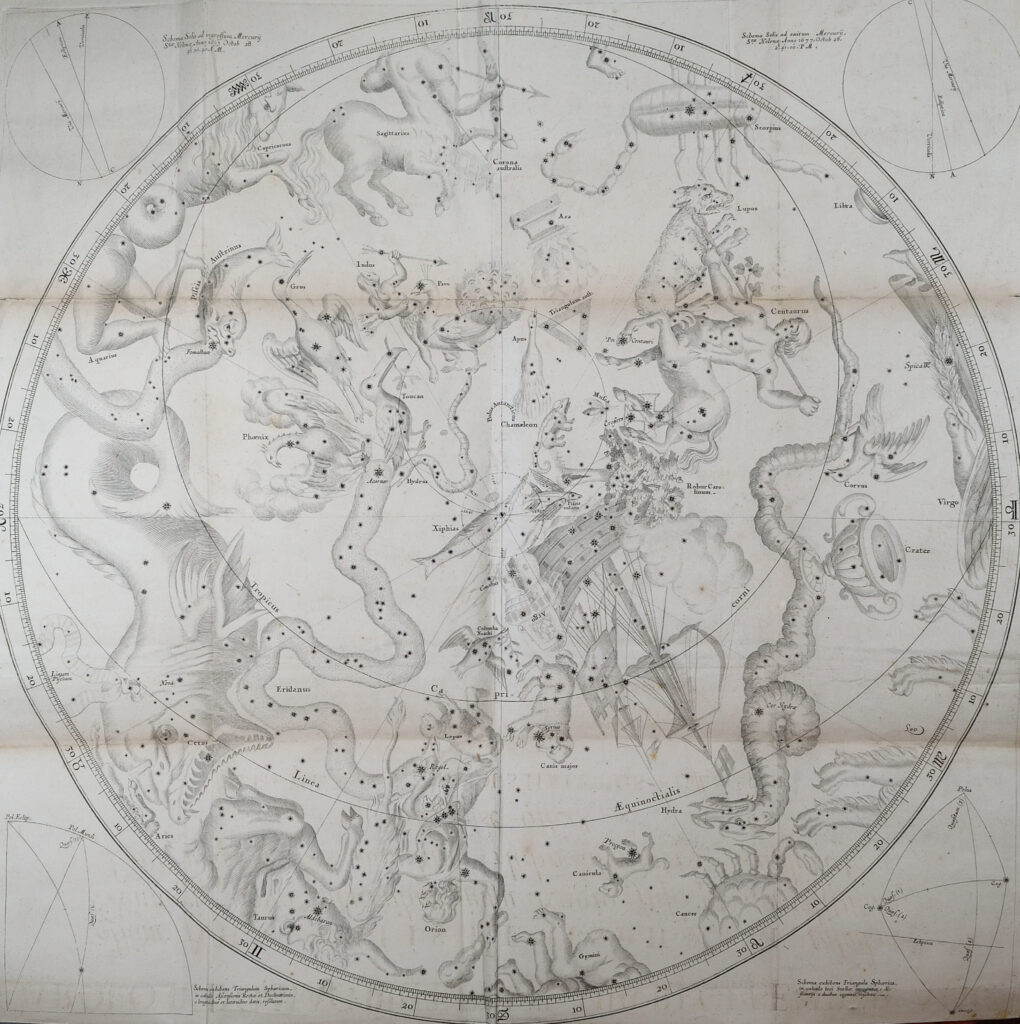

Edmond Halley, Catalogus stellarum australium sive Supplementum Catalogi Tychonici, London, 1679 [Sel.f.163]

The star map shown here also contains ‘Robus Carolinum’ (Charles’ Oak), Halley’s patriotic homage to Charles II’s famous sylvan escape from parliamentarian troops. This now-unrecognised constellation can be seen at the base of the celestial globe at the other end of the Upper Library, under the stained-glass eye of the king in the window above (who was so pleased he ordered the University to confer on Halley the degree of Master of Arts).

‘Mr. Hally’s letter and observation of the same made at St. Hellena’ in Lectures and collections made by Robert Hooke, secretary of the Royal Society, London, 1678 [HS.c.37(6)]

In 1676, before completing his degree, Halley packed up his telescopes and clocks, and sailed on an East Indiaman to the South Atlantic to ‘finish the celestial globe’. During his time on the island of St Helena, Halley mapped 341 stars, observed the transit of Mercury, and realised that the size of the solar system could be accurately calculated in 1769 during the transit of Venus.

Do Look Up!

<p>As the pile of international philately from 1986 shown here suggests, Halley is remembered today largely as a consequence of his eponymous comet, rather than his other scientific work. Halley’s genius was not to spot the comet, but in combining his mastery of astronomical data and Newtonian theory of universal gravitation to predict its path – and hence its return every 75-79 years.</p> <p>While Halley died before the comet could be seen again in 1759, he had the satisfaction of predicting an eclipse in 1715 (now known as ‘Halley’s Eclipse’), and by publishing a chart showing the path of the temporary darkness (printed with John Senex, who, along with his wife Mary, made and sold the three* globes in the Upper Library), that helped both to calm the potentially worried and to demonstrate the predictive power of Newton’s new celestial mechanics.</p>

Edmond Halley, Catalogus stellarum australium sive Supplementum Catalogi Tychonici, London, 1679 [Sel.f.163]

<p>The star map shown here also contains ‘Robus Carolinum’ (Charles’ Oak), Halley’s patriotic homage to Charles II’s famous sylvan escape from parliamentarian troops. This now-unrecognised constellation can be seen at the base of the celestial globe at the other end of the Upper Library, under the stained-glass eye of the king in the window above (who was so pleased he ordered the University to confer on Halley the degree of Master of Arts).</p>

‘Mr. Hally's letter and observation of the same made at St. Hellena’ in Lectures and collections made by Robert Hooke, secretary of the Royal Society, London, 1678 [HS.c.37(6)]

<p>In 1676, before completing his degree, Halley packed up his telescopes and clocks, and sailed on an East Indiaman to the South Atlantic to ‘finish the celestial globe’. During his time on the island of St Helena, Halley mapped 341 stars, observed the transit of Mercury, and realised that the size of the solar system could be accurately calculated in 1769 during the transit of Venus. </p>

‘Behold set out for you the pattern of the Heavens’: Halley and Newton

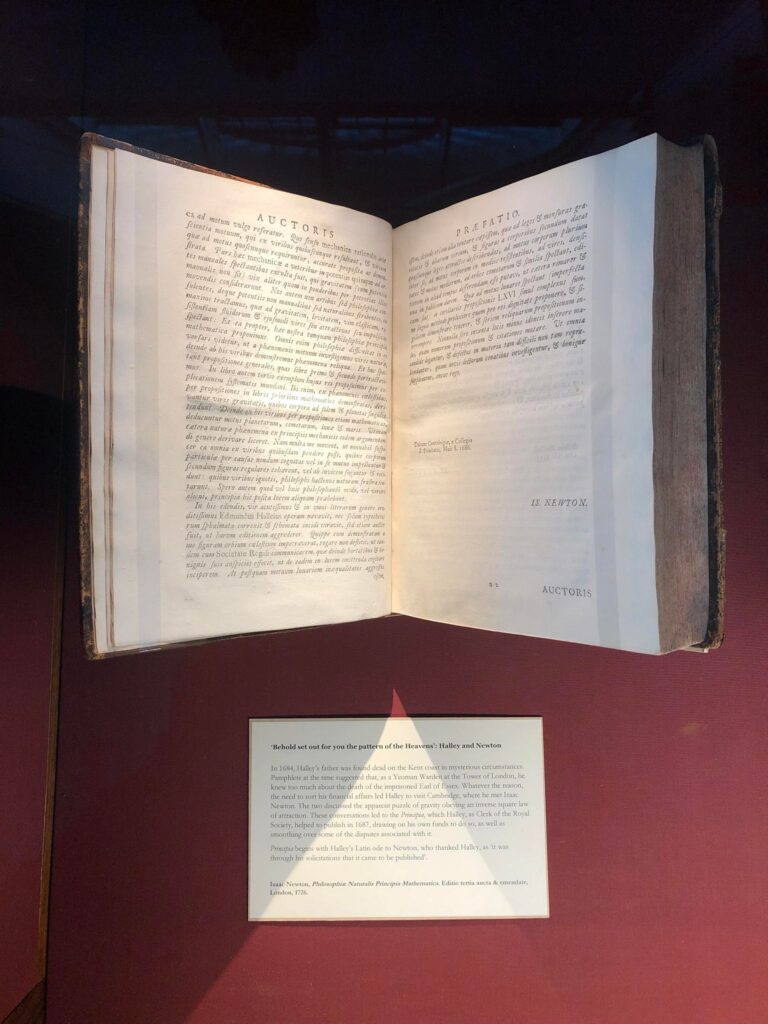

Isaac Newton, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Editio tertia aucta & emendate, London, 1726.

In 1684, Halley’s father was found dead on the Kent coast in mysterious circumstances. Pamphlets at the time suggested that, as a Yeoman Warden at the Tower of London, he knew too much about the death of the imprisoned Earl of Essex. Whatever the reason, the need to sort his financial affairs led Halley to visit Cambridge, where he met Isaac Newton. The two discussed the apparent puzzle of gravity obeying an inverse square law of attraction. These conversations led to the Principia, which Halley, as Clerk of the Royal Society, helped to publish in 1687, drawing on his own funds to do so, as well as smoothing over some of the disputes associated with it.

Principia begins with Halley’s Latin ode to Newton, who thanked Halley, as ‘it was through his solicitations that it came to be published’.

Apollonius of Perga’s Conics

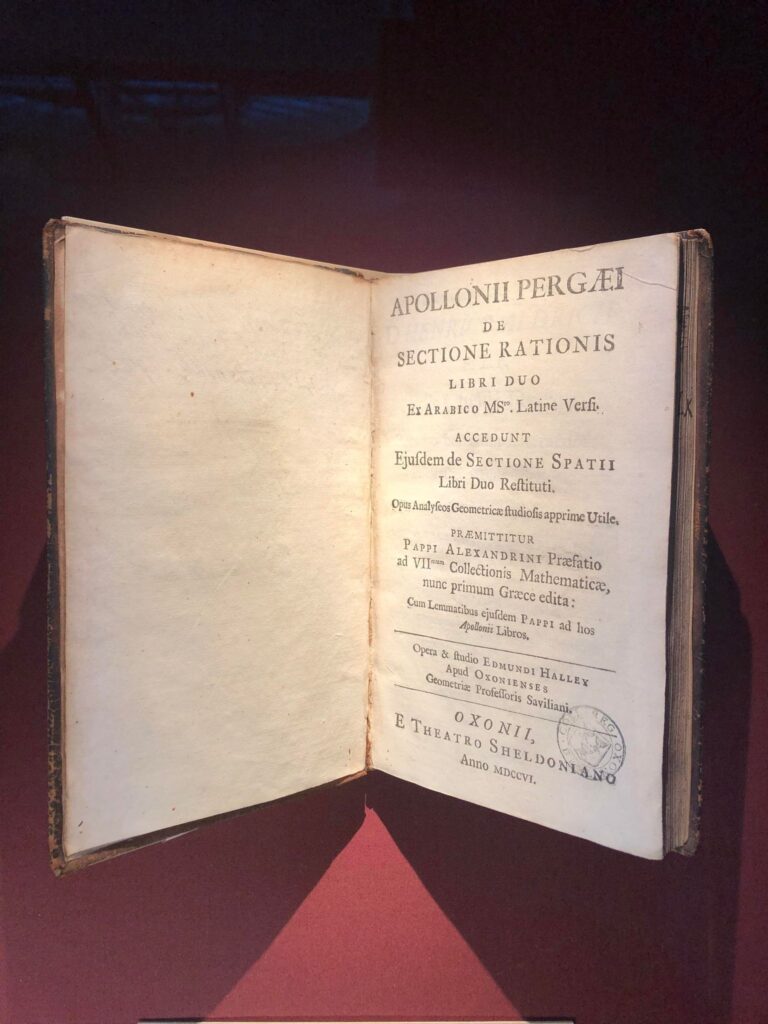

Apollonii Pergæi De Sectione Rationis Libri Duo, Oxford, 1706 [40a.b.8]

Elected to the Savilian Chair of Geometry in 1726, Halley took up residence in New College Lane (the house can still be seen, topped by Halley’s small observatory). Halley began a translation and reconstruction of Apollonius’ Conics, drawing on his linguistic knowledge, including Arabic. Apollonius’s conics helped with the derivation of orbits; as one of Halley’s biographers notes: ‘In Halley’s day it had the very important additional significance that is was one of the bases of Newton’s methods in the Principia’. While the mathematics moved on, Halley’s work resurrected and preserved ‘a work of intellectual depth and elegance’.*

Francis Godolphin, 2nd Baron Godolphin gave this copy (which then cost 4s 6d) to the College Tabarders’ library in 1726.

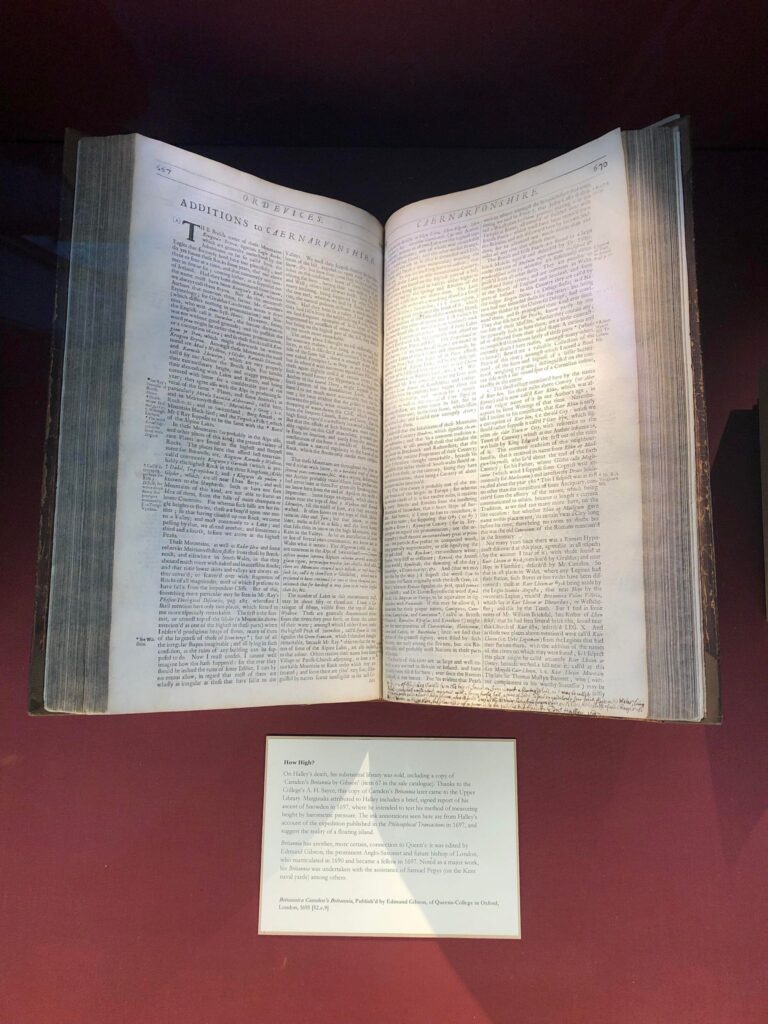

How High?

Britannica Camden’s Britannia, Publish’d by Edmund Gibson, of Queens-College in Oxford, London, 1695 [52.e.9]

On Halley’s death, his substantial library was sold, including a copy of ‘Camden’s Britannia by Gibson’ (item 67 in the sale catalogue). Thanks to the College’s A. H. Sayce, this copy of Camden’s Britannia later came to the Upper Library. Marginalia attributed to Halley includes a brief, signed report of his ascent of Snowden in 1697, where he intended to test his method of measuring height by barometric pressure. The ink annotations seen here are from Halley’s account of the expedition published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1697, and suggest the reality of a floating island.

Britannia has another, more certain, connection to Queen’s: it was edited by Edmund Gibson, the prominent Anglo-Saxonist and future bishop of London, who matriculated in 1690 and became a fellow in 1697. Noted as a major work, his Britannia was undertaken with the assistance of Samuel Pepys (on the Kent naval yards) among others.

Explore more of our exhibitions

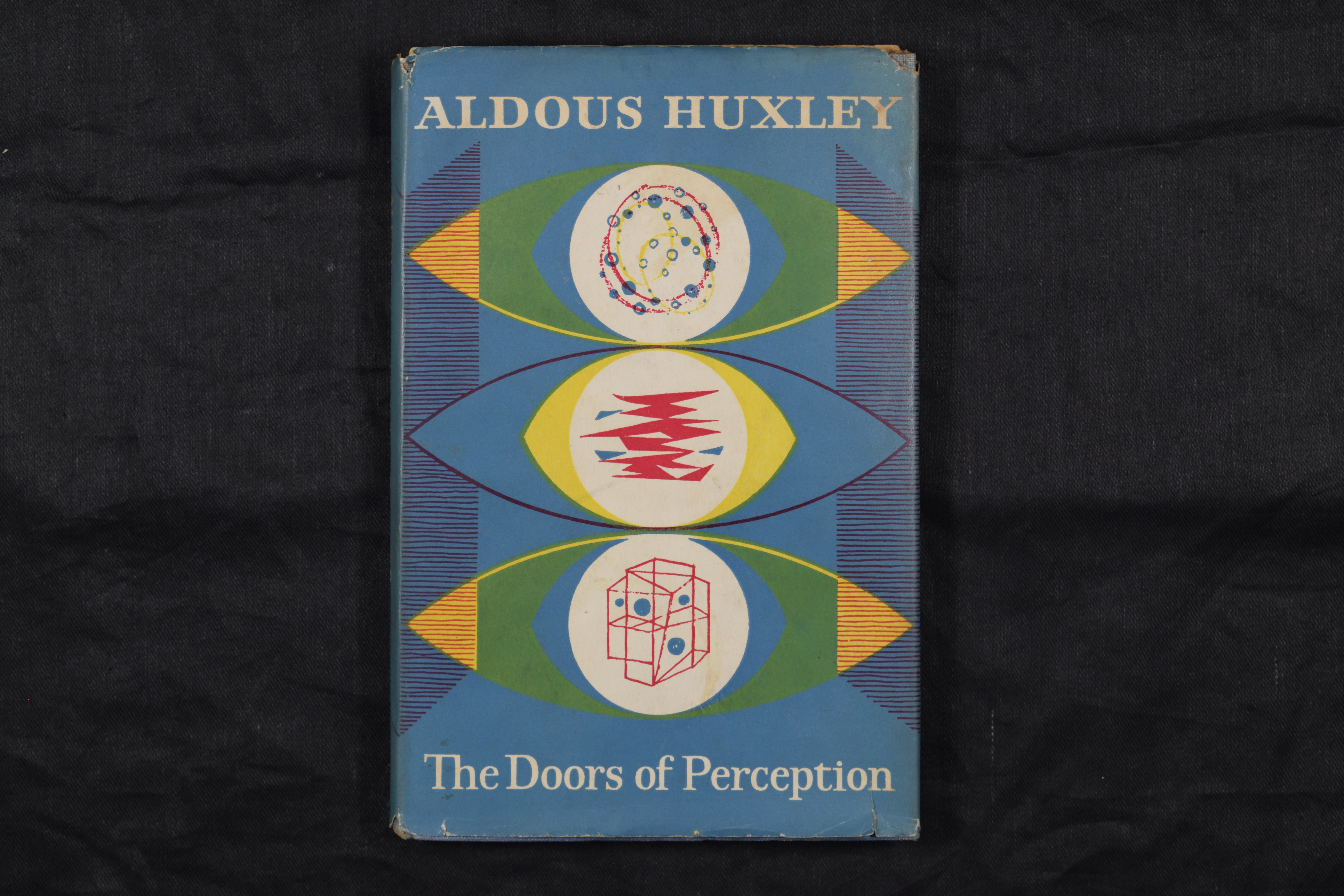

Perception: an exhibition

‘From the author’

Joseph Williamson and the establishment of the transatlantic slave trade