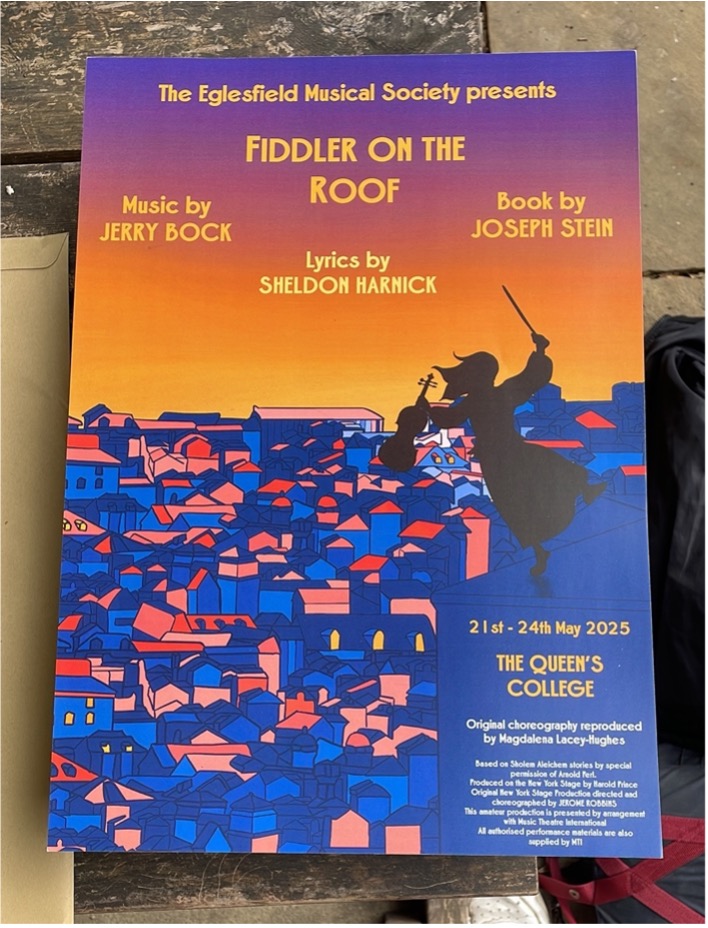

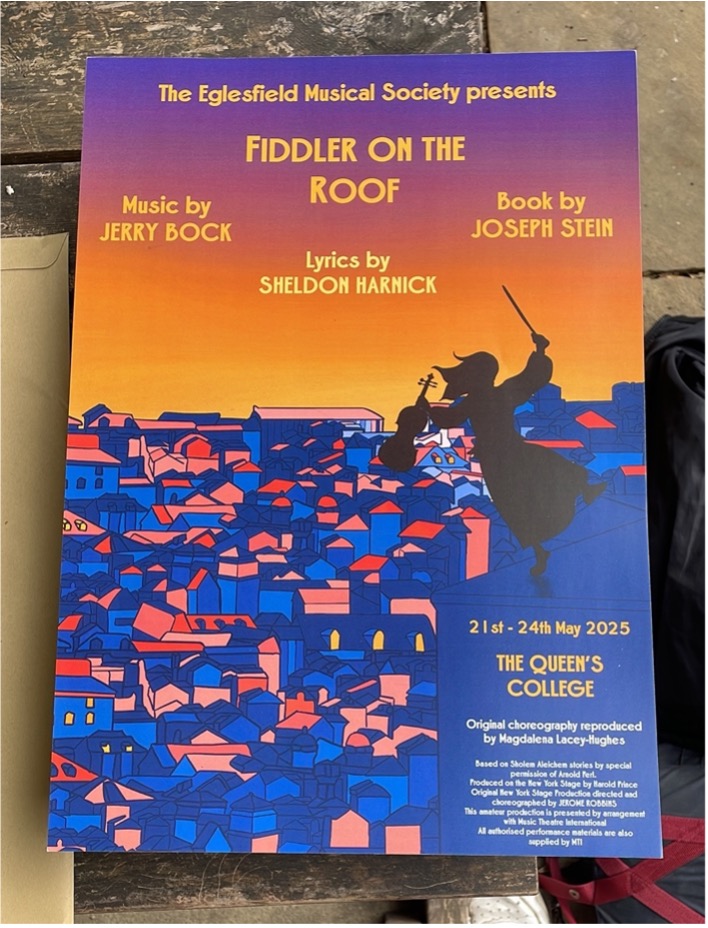

The Eglesfield Society’s summer show is an annual highlight in the Queen’s Trinity Term calendar of events. This year, the College gardens provided the backdrop for Fiddler on the Roof. This student-led production brought together around 70 students from across Oxford, including visiting students from the US, with a diverse and enthusiastic cast and crew drawn from over 15 colleges. Producer Matilda Bates tells us more.

This year the show was Fiddler on the Roof, a beautiful and timeless story about the struggles of a Jewish community in 1905 Tsarist Russia to reconcile tradition with change, amidst growing threats of violence and displacement. We felt this was an important story to tell in today’s international climate, and the gardens of The Queen’s College provided a perfect location.

Putting on a production of this scale is a massive undertaking. The show was entirely student-led, relying on the talent and skill of the student community. Around 20 members of Queen’s were involved as members of the cast, production team, and band, and we also collaborated widely across the University. Our directing team came from Trinity and Magdalen, and the cast included students– both undergraduate and postgraduate– from over 15 different colleges. We were also delighted to welcome several visiting students from the US. For some of our company, this was their first experience of putting on a musical, while others were seasoned performers and technicians. Altogether, nearly 70 students were involved, making it a large collaborative effort across the University.

The show required lots of time and effort over Hilary and Trinity terms. We rehearsed throughout the second half of Hilary, then had an intense week of rehearsals in 0th week of Trinity known as bootcamp, where we put together the big numbers with music and choreography. Everybody worked so hard and we all had so much fun – it was a great opportunity for the cast to really get to know each other. Another highlight of the process was the sitzprobe, where the cast and band met for the first time to sing through the show. It was amazing to hear everything come together, leaving everybody excited for show week.

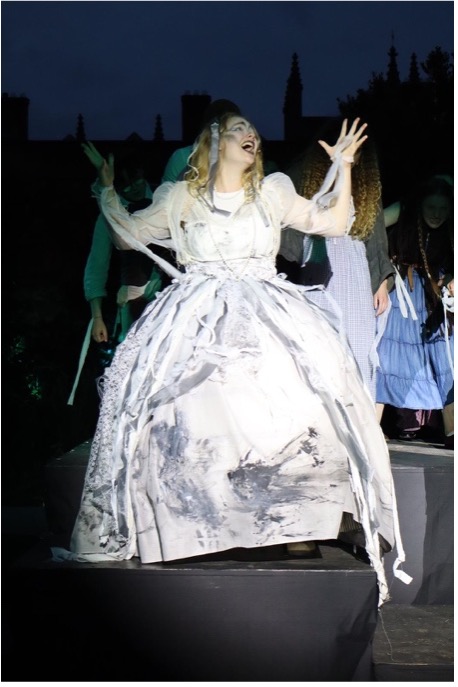

Show week was the busiest week of my time in Oxford. Preparing for the show was a full cast and crew effort: unloading and constructing staging and tech, setting up the garden, transporting costumes from the National Theare, and transporting props across Oxford on a trolley (we got some funny looks from members of the public!). People had so many skills, and they were all put to great use. For example, one of our cast members is an excellent seamstress and made a beautiful dress for Fruma Sarah to wear in The Dream (pictured below). Our tech team, crew, and publicity team were all absolutely excellent, and every person was an invaluable member of the team.

All five performances were a triumph. The staging and lighting looked beautiful in the garden, and it got dark as we went into the second half, making the lights even more striking. We made record ticket sales thanks to our incredible publicity team, having to run to find more chairs because it was so crowded! We were reviewed by a number of student publications and received high praise: the choreography especially receiving frequent commendation. The threat of rain loomed all week, but thankfully it held off until the final performance. The rain was light enough that we could continue, and it added a level of poignancy and drama as the story reached its climax, so worked nicely. Overall, we had an incredible reception from our audiences, which made our hard work seem extremely worth it!

I want to extend huge thanks to everybody who supported the production. First, thanks to the generous support from funding bodies, especially to the Walter Pater Grant, the 650th Anniversary Trust Fund, and Queen’s JCR Arts Fund: their support made this production possible. Second, massive thanks to our director, whose creativity and dedication brought the show to life, alongside taking her finals! Thanks to the amazing tech team, who made everything run so smoothly. And finally, thanks to everyone at Queen’s who made this happen: Sarah Daley, the Conferences team, and the Lodge for making everything run so smoothly. We all had the best time bringing this beautiful story to life: it was an experience we’ll never forget!

Matilda Bates

Exec team

Director: Hannah Davis

Assistant director: Phoenix Barnett

Choreographer: Magdalena Lacey-Hughes

Co-musical director: Kyle Siwek

Co-musical director: Tom Constantinou

Producer: Matilda Bates