In this blog for The Queen’s Translation Exchange, Dr Mary Boyle (Linacre College) explores the place of often violent medieval literature in children’s literature.

Knights and dragons are such a fixture of children’s literature that they seem to find their way into the least medieval settings imaginable. Not only is there even a Postman Pat episode on the topic but, since I started writing this, I’ve discovered that there are two. But have you ever stopped to think about how strange this is? Dragons are bloodthirsty monsters, while the business of knights is, well, violence. It might be characterised as violence in the service of their country, or to protect damsels in distress, but it’s violence nonetheless. The purpose of those swords isn’t simply to shine, but to kill – or at the very least, to threaten to kill. And yet we think of these characters as not just child-friendly, but obvious material for children’s stories. Why?

Fitting knights and their world into children’s literature isn’t a new idea, but goes back well over a hundred years, to Victorian and Edwardian children’s authors who made use of medieval texts in their search for new material for young audiences. Drawing on the past is never politically neutral, and it certainly wasn’t for these writers, who were getting involved in a contemporary passion for the Middle Ages which was so influential that many of the things we think of today as medieval are actually products of the nineteenth century. So why wasn’t this politically neutral? Countless words have been written about this, but to cut a long story short and then simplify it, there was a desire to identify the beginnings of English culture and democracy in a pre-Norman-Conquest past which was shared with other supposedly ‘Germanic’ (itself a complicated and loaded term) regions like Germany and Scandinavia. Given this background, maybe it’s not surprising that writers at the time decided that the Nibelungenlied, a thirteenth-century German epic, which also exists in various different Scandinavian versions, would make a perfect children’s book. After all, it featured not only those knights and dragons, but also other fairy-tale staples like kings, queens, princes, princesses, treasure, prophecies, and battles.

Unfortunately, the Nibelungenlied also has pretty non-child-friendly features: sex and sexual violence; betrayal and (mass) murder; the decapitation of a child; burning people alive; drinking blood from corpses; the parading of the decapitated head of one prisoner in front of another; the beheading of an unarmed man; and – to close proceedings – the brutal killing of a woman. Basically, the knights behave like the warriors they are – but it’s worth pointing out that, generally speaking, the violence itself wasn’t exactly a problem for our writers. The real issue was that much of the violence is directed (and partly carried out) by a woman, our main character, Kriemhild, as we’ll see if we take a closer look at the story.

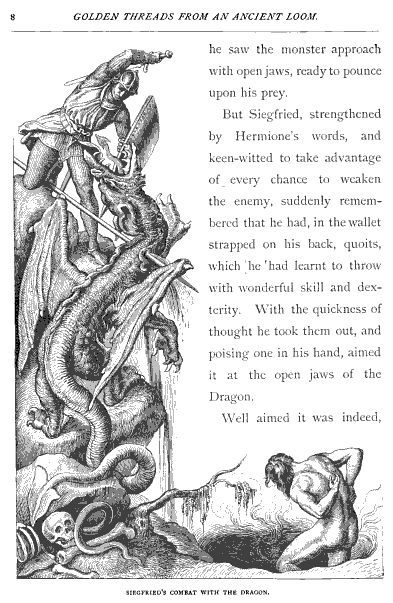

In the first part of the narrative, a brave prince called Siegfried, after killing a dragon and acquiring various superpowers, marries a beautiful young princess named Kriemhild. However, after ten years of living happily ever after, Siegfried is murdered by Kriemhild’s relation, Hagen, with connivance from her brother, Gunther – an unimaginable betrayal – and his body left outside her door. For good measure, Hagen also has Kriemhild’s treasure, a gift from her dead husband, stolen and sunk in the Rhine. The second half covers Kriemhild’s decades-long search for revenge and its exceptionally bloody climax. After being complicit in the deaths of hundreds of men, not to mention her own child, whom she uses as bait to get the violence underway, Kriemhild orders Gunther’s death and decapitates Hagen herself – at which point she’s hacked to pieces by a bystander, who is outraged at seeing a knight (however wicked) killed by a woman.

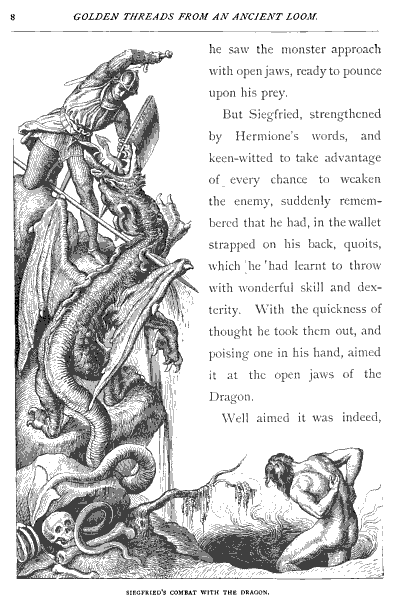

Turning the Nibelungenlied into a children’s story obviously wasn’t going to be just a matter of translating it from Middle High German into English and putting it in the hands of young Victorians. The mostly fairy-tale-like first half of the narrative was quite easily adapted for children, but the second part presented many more problems because the plot basically follows Kriemhild’s violent quest for revenge. Now admittedly, it could have been worse – the Scandinavian material features the female protagonist killing her children, baking them into pies, and serving them to their father. At least Kriemhild’s limit was putting her son in a situation which she knew would lead to his death. One common solution was only to adapt the first part, perhaps summarising the revenge plot in a few sentences. These adaptations would usually bring in some Scandinavian material, which had the advantage over the German version that the fight with the dragon didn’t take place ‘offscreen’. This particular violence only involves a man and a monster, so it could appear in its full gory detail, including Siegfried’s post-fight bath in the dragon’s blood. But there were some writers who decided that they were just going to go for it and adapt the whole thing. Let’s take a look at two of them.

First up, Lydia Hands, author of Golden Threads from an Ancient Loom, subtitled Das Nibelungenlied, adapted to the use of young readers. She was ahead of the curve by publishing in 1880 – most English-language children’s adaptations of the Nibelungenlied came along after the English premiere of Wagner’s Ring cycle in 1882 drew attention to the material. Hands deals with the difficulty of translating Kriemhild’s violence by finding an explanation which would make (legal) sense to her audience: Kriemhild was mad with grief at the death of her child. You’re probably thinking that this is a bit rich of Kriemhild, since this is entirely her own fault. So Hands simply neglects to translate that part of the text. In her version, the boy’s death comes as a terrible shock, causing Kriemhild to faint in horror. When she wakes up, ‘a frenzy, as of madness, possessed Criemhild; her enemy should not escape, even though her own life should be the penalty’. Then she orders the hall to be burned down with hundreds of men inside. It’s the death of her son that triggers Kriemhild’s madness, and her madness which triggers her indiscriminate violence. Insanity was a routine defence in nineteenth-century law courts, and it means that Hands can keep all the violence – and she really does – without undermining contemporary expectations of women. It doesn’t excuse Kriemhild, and she doesn’t get a happy ending, just a marginally less violent death, but it relieves her of her moral responsibility and any knock-on consequences for society.

This wasn’t enough for Gertrude Schottenfels in Stories of the Nibelungen for Young People in 1905. There’s no violent death for Kriemhild’s son, and Kriemhild herself is kept at some distance from the violence. Eventually, Hagen and Gunther are brought to her by a knight, who makes her give ‘her word of honor that he, and he alone, should be permitted to put them to death’. So really, when Kriemhild orders them to be beheaded ‘according to the custom of these olden times’, she’s just following a knight’s suggestion. This Kriemhild is allowed to live, and the closest we get to a condemnation is being told that she was ‘once gentle and beautiful’, implying that she no longer is. But she’s neither dead nor disgraced, and the spectacular body count isn’t attributed to her.

Maybe this is as close as we get to an answer to my starting question. Compared to the other violence in the Nibelungenlied, knights’ (and dragons’) violence isn’t considered a big deal. As long as you can translate away the unacceptable violence, you can keep the rest – no matter how extreme.

Mary Boyle is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and a Junior Research Fellow at Linacre College, Oxford.