Dr Matthew Shaw, Librarian

In their striking gold, crimson, and azure ceremonial tabards, heralds have processed across our TV screens on several occasions in recent months, acting as colourful, even theatrical, reminders of the ancient origins of our constitutional arrangements. Their origins lie in the organisation of medieval tournaments: acting as a kind of umpire, arranging the contests and keeping a tally of the score. As such, they became expert in the arms and crests worn by the knights participating in these events, and became recognised authorities in heraldry and the organising of ceremonial events.

In 1484, Richard III gave the royal heralds a charter of incorporation along with a house by the Thames in the City of London. This College of Arms granted new coats of arms and offered advice on state ceremonies, genealogy, and other matters of precedence. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries heraldic visitations dispatched them to the corners of the kingdom to establish the status and genealogies of noble families and record and check coats of arms, creating a mass of paper records. Many of these manuscripts are held by the College of Arms, but a significant number of important heraldic volumes and rolls initially gathered by antiquarians are now held by Queen’s College Library.

In May 2023, the College is hosting an Old Members’ event at Stationers’ Hall, London. It will include a panel comprised of English Literature Fellows, the College Librarian, and the actor Alfie Enoch (an Old Member), discussing Shakespeare in this, the 400th anniversary of the publication of the first folio edition of Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (registered at Stationers’ Hall in November 1623; the College possesses copies of the first four editions of the folio).

Shakespeare understood the importance of heraldry, and how his countrymen and women would read it. Heraldry had currency both as metaphor and a useful signifier of power and social status, as well as its fragility (and perhaps pomposity). It is significant, for example, that when Henry Bolingbroke sentenced the king’s councillors Sir John Bushy and Sir Henry Green to death in the play Richard II, ‘unfold[ed] some causes’, he describes how

You have…

From my own windows torn my household coat,

Razed out my impress, leaving me no sign,

Save men’s opinions and my living blood,

To show the world I am a gentleman (Richard II, Act III, Scene 1)

Bolingbroke’s loss of his coat of arms in his banishment is used to underscore the shame inflicted upon him. Elsewhere, the anonymous Edward III, at least in part the work of William Shakespeare, is distinguished by its use of heraldry, helping to signal the play’s concern for lineage (such as in the heraldic riddle, ‘the time will shortly come/Whenas a lion rousèd in the West/Shall carry hence the fleur‐de‐lis of France’ (Edward III, Act 3, Scene 2, lines 41–3)). The play is full of the visual language of these devices ‘of antique heraldry’, their specificity and richness suggesting that Shakespeare may have been familiar with medieval chronicles illuminated depictions of battlefields:

and Straight trees of gold, the pendants, leaves,

And their device of antique heraldry,[1]

Quartered in colours seeming sundry fruits,

Makes it the orchard of the Hesperides. (Edward III, Act 4, Scene 4, lines 25–9)

Elsewhere, in Hamlet, the prince signifies the cruelty of Pyrrhus, his ‘dread and black complexion smear’d/With heraldry more dismal… horridly tricked/

With blood of fathers, mothers, daughters, son’ (Hamlet, Act II, Scene II). While in Othello, Cassio reaches for the metaphor of heraldry (blazon) to describe the beauty of Desdemona, ‘One that excels the quirks of blazoning pens’ (Othello, Act II, Scene 1, line 69).

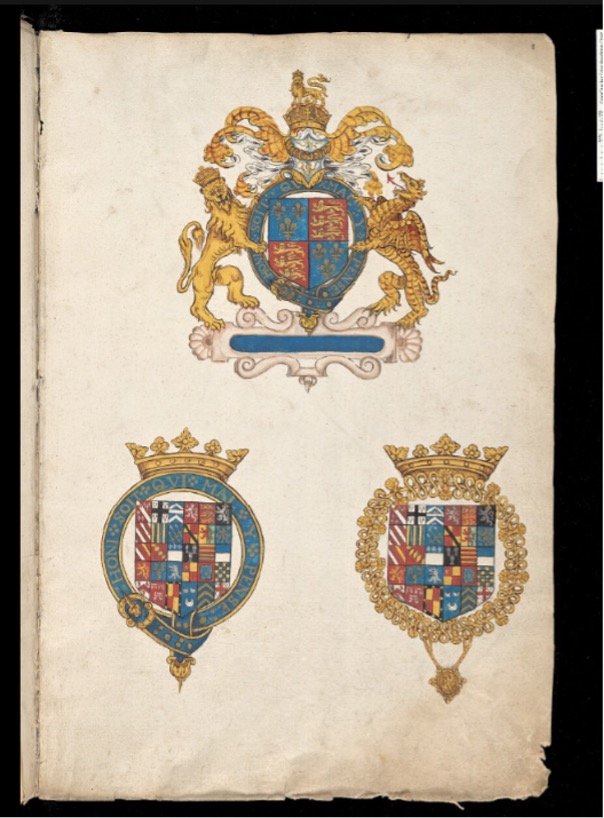

Two of the College’s heraldic manuscripts are brought to mind as we consider Shakespeare and heraldry. The first is the earliest record of the coat of arms for the City of London, drawn in 1568 by Robert Cooke (d. 1593), the Clarenceux King of Arms, and now resplendent in Queen’s MS 72. Thanks to the generosity of the College of Arms, it has been digitised, and can be viewed online via the Digital Bodleian (where it can be viewed alongside a growing number of other treasures from the College Library). Noted for the prodigious number of arms that he granted, and its resultant lucrative trade in fees, his tenure was a troubled one, marked by a dispute between him and the Garter King of Arms about the rights to visitations throughout England. For his part, as the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography notes, Cooke argued that the ‘decaying nobility possibly envied men of mean birth whose virtue none the less outshone the older aristocracy’s.’[2]

![The arms of [the] Citie of London, Queen's MS 72. Image: The Provost and Fellows of The Queen’s College, Oxford. CC-BY.](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/citie-of-London-arms.jpg)

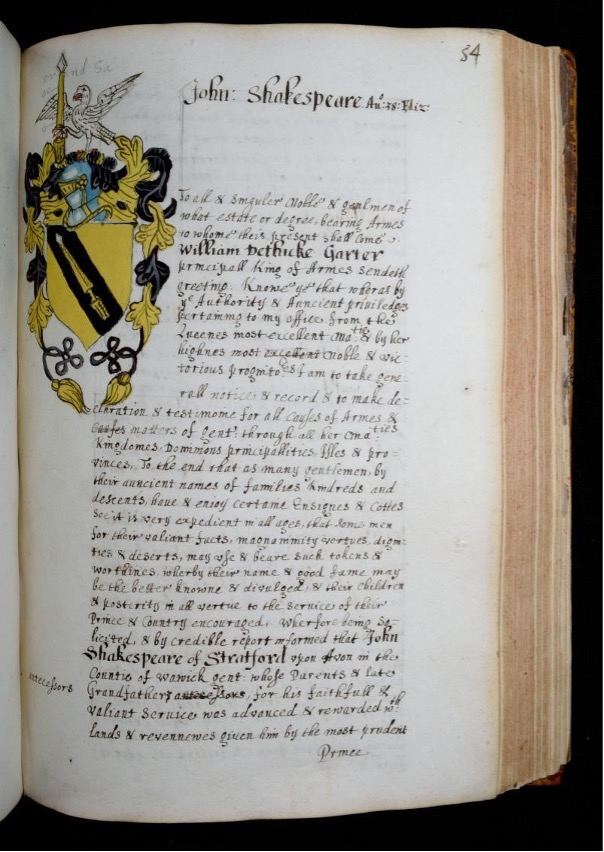

The other coat of arms is a reminder not of the city with which Shakespeare is so closely associated, but of his family – and the importance that a mark of gentility could play in Early Modern England. While gunpowder and other military technologies had made the knight’s shield and armour largely redundant, Elizabethan England displayed a fascination with the ‘colourful paraphernalia of heraldry’. Such concerns might also be related to the obsession with patriarchal family structures that some historians have argued characterised the period.[3] Shakespeare’s father, John, first attempted to obtain a coat of arms in 1575 to reflect his status in Stratford-on-Avon, but his financial situation prevented him from doing so. Following his commercial success, William Shakespeare successfully renewed the efforts in 1596 with the Garter King of Arms, and so consolidating his own importance as he did. As Heather Wolfe, the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, has shown, ‘while Shakespeare was obtaining the arms on behalf of his father, it was really for his own status.’ A coat of arms was a sure signifier of success. As seen below, Queen’s is fortunate to hold a late-seventeenth century copy of this grant, with the text almost identical to the earlier, second draft.[4]

Such social climbing could of course backfire. Ben Johnson, Shakespeare’s contemporary and literary competitor, mocked the coat of arms in his play, Every Man Out of His Humour (1598; registered at Stationers’ Hall in 1600), in which the ‘vain-glorious knight’ Puntarvolo suggests the clownish Sogliardo’s new arms should have the motto ‘Not Without Mustard’. Shakespeare’s arms, which as we see here are Colman-bright, and usually has the motto Non Sanz Droict (‘Not Without Right’).[5] In a more poetic mode, Cassio’s description of Desdemona above (‘One that excels the quirks of blazoning pens’), draws on fairly novel use for Shakespeare’s time of blazon in English, suggesting both ‘description in heraldic language’ as well as to ‘describe fitly’ (OED), placing such ‘devices of antique heraldry’ in the shade of Othello’s doomed wife’s beauty.

Arms continued to be used in the Shakespeare family, until his last direct descendent, Elizabeth Barnard, died in 1670. A fragment of the Shakespeare arms can just be seen in the wax seal on her will, serving as a mark of status for this one last occasion.[5]

References

[1] Anny Crunelle Vanrigh, ‘Illuminations, Heraldry and King Edward III’, Word and Image, no. 3 (2009), pp. 215-231.

[2] J. F. R. Day, ‘Cooke, Robert’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6148

[3] Arthur B. Ferguson, The Indian Summer of English Chivalry: Studies in the Decline and Transformation of Chivalric Idealism (Durham, N.C., 1960), p. 17, quoted in Nancy J. Vickers, ‘This Heraldry in Lucrece’ Face’, Poetics Today 6, no. 1/2 (1985), p. 172.

[4] See also shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/resource/document/john-shakespeare-s-grant-arms.

[5] Jennifer Schuessler, ‘Shakespeare: Actor, Playwright. Social Climber,’ New York Times, 29 June 2016. The will can be seen at shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/file/details/693.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)