Professor Richard Bruce Parkinson, Professor of Egyptology

The oldest item on display in the New Library is an Egyptian papyrus from around 650 BCE that was identified in the Upper Library in 1997 by the then Professor of Egyptology, John Baines. It had been mounted on linen at an unknown date, and then on paper in the 1840s, and unsurprisingly needed conservation treatment. John contacted me, as I was then curating the papyri in the British Museum, and I immediately spoke to a close friend and museum colleague, Bridget Leach, internationally renowned as a specialist papyrus conservator.

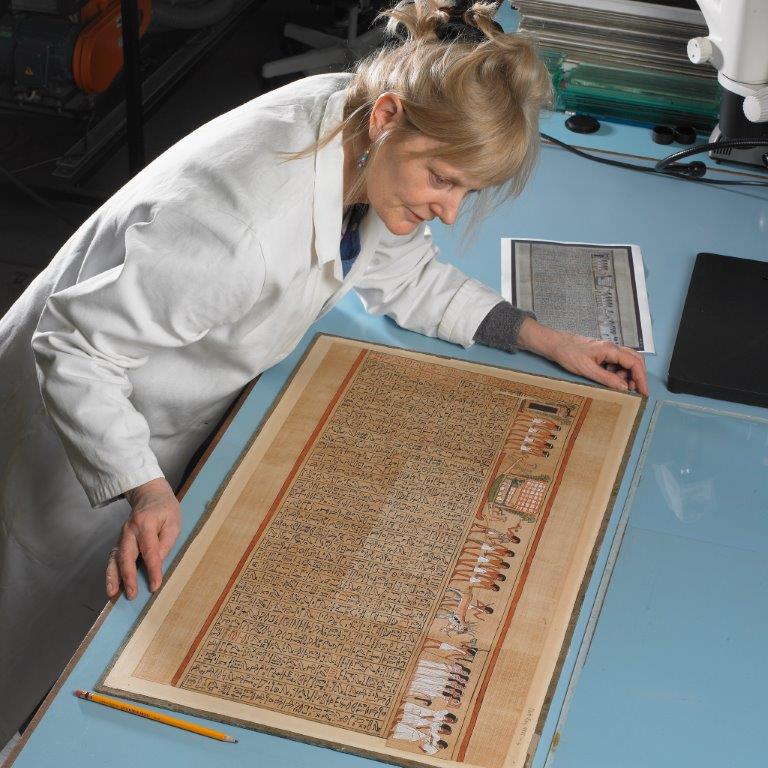

The papyrus was brought to London and she undertook its treatment in the museum’s conservation studio, removing the papyrus from its old backing, and revealing a text written on the back. The process was slow and delicate; repairs, cleaning and flattening were carried out, and numerous fragments were replaced in their correct positions. When a papyrus is placed on a light table the distinctive pattern created by the papyrus plant fibres becomes visible, and this pattern helps fragments that join to be identified (like the pattern on a jigsaw). As Bridget (pictured below) worked, the texts were being studied from photographs by Prof Hannes Ficher-Elfert (Leipzig) and Gunther Vittmann (Würzburg), and most of the fragments were re-joined, with the unplaceable ones being mounted in a group to one side. Because of the difficulties posed by the texts, which are written in the rare ‘abnormal hieratic’ cursive script, this process lasted from 1999 to 2009, and Hannes came to London to examine the papyrus on several occasions.

The papyrus was then mounted between two sheets of glass, and Bridget and I decided on a frame. Although Papyrus Queen’s is extremely important, it is not one of the most visually appealing papyri, so we chose a very elegant simple wooden frame, which as it turns out matches the style of the New Library. The papyrus came back to Oxford in 2013 when I moved office from the British Museum on taking up post in Oxford (saving some extra transport costs).

Papyrus is an organic material, which is very light-sensitive, like paper.

Papyrus is an organic material, which is very light-sensitive, like paper. Prolonged exposure will cause irreversible damage to the cellulose and lignin, the principal components of papyrus which takes on a ‘bleached’ appearance. Once the surface becomes weakened in this way, the text is also endangered, as the surface of the papyrus with the ink breaks up. For this reason, the papyrus will not be on permanent display, but after a year or so will return to storage in the Ashmolean Museum to join with the majority of the Queen’s College collection of Egyptian antiquities. They are kept with the Ashmolean’s own collection and can be consulted by appointment in the Museum’s study rooms: the early backing and Bridget’s full report on the conservation are now kept in the College Archive for anyone wanting to investigate the history of its acquisition. The study of the text on the papyrus is now complete and the publication is being planned.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)