Rhodes Scholar Tori Harwell (Missouri and Queen’s, 2024) is a passionate researcher and advocate for environmental justice with a strong commitment to global Black communities.

During Tori’s latest research project as a Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow, they focused on cocoa cash crop farming in Ghana, employing auto-ethnography and archival research to explore the impacts of colonialism in Kukurantumi, Ghana. Tori’s work is grounded in community-based projects that address the lack of infrastructure supporting Black communities working to heal their connection to the land itself. As a Goldman Fellow, Tori developed a dual-strategy project to connect Black urban famers in St. Louis with free legal support while addressing their immediate capacity needs. We asked Tori to explain the impact of their research and tell us what they enjoy about being at Oxford.

You read African and American Studies and Environmental Analysis at Washington University in St Louis. What have been some of the big differences between studying at Oxford compared to back at home?

There are plenty of differences! I didn’t understand the college system at all, at first. Queen’s chose me in a sort of great sorting hat moment. I’m very happy to be here and have found friends from all different subject areas. At Oxford, I think you can deeply question one subject, and the tutors don’t give you an answer but lead you to more questions. You have the capacity to make your experience here what you want it to be.

At Oxford, you can deeply question one subject, and the tutors don’t give you an answer but lead you to more questions.

You apply queer and black theoretical frameworks to cocoa farming practices in Ghana. Can you tell us a bit about what you have discovered by doing this?

My research has been guided by the community that I’m working with, I don’t assume people are black or queer, but I use specifically black/queer rhizomatic frameworks to understand kinship ties — how someone like me, who has no direct connections to the African continent due to slavery, can still connect back in through family structures that are not visible to people who live in a nuclear family.

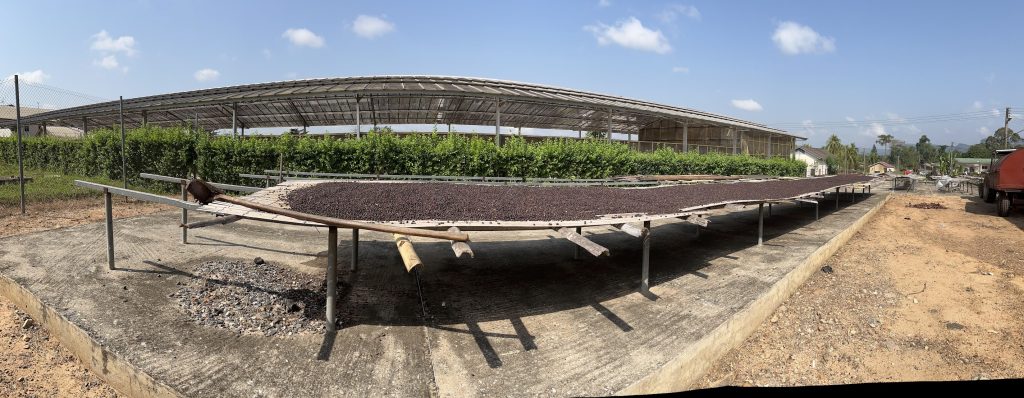

I didn’t go to Ghana thinking I’d be studying chocolate, but I was asking questions about environmental degradation in the region and time and time again people would mention chocolate. I then went to the Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana. There was a dream present there but also conflict. So much of chocolate’s history in Ghana is one of liberatory practices and it’s causing environmental degradation. Chocolate’s material history going from Tetteh Quarshie, the Ghanaian man who brought cocoa to the Gold Coast, to the idea of a large factory mogul, the Cadbury Firm from Europe, who came into Ghana and reorganised the space. And now it’s one of the few crops you can sell to build limited generational and social wealth for families. I am interested in how those two stories align with each other and the ways in which people engage with land and one another. I want to explore the overlapping outgrowth of their dreams and intentions for that same space.

What motivates you in your research?

I want to know why the narratives we have around climate change are the majority narratives and how colonisation continues to exist in the way that we interact with places and people. I think it’s at the essence of Oxford but in Ghana and South Africa, capitalism, racism, and colonization are at the organisational core of a lot of our current systems. I don’t think we can truly create climate adaptations or mitigations without deeply questioning those systems. For example, we need to question whether we should even continue with monocrops like chocolate.

Farmers are wrapped up in the consequences of this history too. Often, cocoa farmers and researchers will speak of the industry with great pride in spite of the fact that chocolate is not indigenous to Ghana. Ghana is the second largest producer of chocolate worldwide, but Ghanaians don’t see the majority of the wealth that comes from this industry because that lies with European chocolatiers. There’s an argument to stop exporting raw cocoa and instead produce chocolate bars in Ghana. The Fair Trade scheme helps somewhat, but I don’t think anything will be fair unless the people who are farming see the majority of the profit which is currently made in the sales, not in the production of the raw material. Fair Trade makes the current system fairer, but the current system itself will never be fair.

What’s the value of interdisciplinary research?

Other disciplines have shaped how I do what I do. I have applied theoretical frameworks from different areas to material history. I think when you start engaging with people who are coming at problems from different perspectives, you see that there’s actually a lot of crossover in the questions that we’re asking. I think everyone has something that they’re really focussing on but by having those conversations you can bridge gaps in a way that you can’t if you’re siloed. It’s hard, though, because there are a lot of different fields to read so I think it’s best if you work among team members. I’m excited to engage in research with people who are doing things across the world.

I think when you start engaging with people who are coming at problems from different perspectives, you see that there’s actually a lot of crossover in the questions that we’re asking.

During your undergraduate studies, you have advocated for accessibility to complete humanities research by minority students. Can you tell us a bit about that work?

At my previous institution I worked at the Office for Undergraduate Research and helped people who wanted to get into research figure out how to go about it. This might mean applying for fellowships or funding and putting your ideas into words effectively to make proposals for this. In my work I found, a lot of the time, the epistemologies and ontologies of minority groups are wholly disregarded so it’s important to have their voices in research. Often the ways their communities engage with the world isn’t present in the academy and it’s extremely important to me to make research accessible to all. As much as I love my work in Ghana, I find myself questioning why only 1% of global research output is by Africans.

How does your project connecting Black urban farmers in St. Louis with free legal support help to address both structural racism and the climate crisis?

The summer before I went to Ghana, I was working in St. Louis with black farmers and connecting them to free legal resources. The way I see it, these farmers are at the forefront of climate mitigation and adaption. Their efforts create tree canopy cover, and their work improves water absorption in the city which helps alleviate flooding because a lot of the concrete infrastructure gives rise to water run-off which exacerbates the flooding problems in the region. These Black farmers are at the forefront of climate mitigation and we should support them. In the US, as well as in Ghana, the number of Black farmers has been decreasing because there are lots of structural inequalities, such as not being able to get access to USDA loans.

One farmer I worked with was share-cropping so he didn’t own the land he was farming. I spoke to my boss at Great River’s Environmental Law Center, a not-for-profit law firm, about this situation and we discussed what legal support might be beneficial. This led to the farmer looking at his leasing contract and, after taking the free legal advice, he managed to negotiate a better deal. This impacted on his ability to continue farming in the same location. Another Black farmer was arrested for protesting the inaccessibility of locally grown organic foods in the grocery stores. The store called the police which resulted in him being given a ‘disrupting the peace’ charge, which meant he faced jail time. The legal team were able to meet the judge and explain the context, improving his legal outcome.

The project targeted some of the most unprotected people but also some of the people doing the most valuable work. And an important part of it for me was that the work should continue after my project finished. My boss continued providing legal aid for the farmers to continue to create sustainable change.

You participated on a panel event at Rhodes House that examined the impact of colonialism and racism on the climate emergency. What have been your first-hand experiences of this impact on your work in Ghana?

In Ghana, like in St. Louis, I also saw that the farmers, perhaps unknowingly, are at the forefront of climate mitigation. In tropical climates, topsoil formation can take a lot longer. So what the farmers plant, like trees and other shrubs, is incredibly important to reduce soil erosion and increase water absorption during monsoon season. Yet, currently in Ghana’s Eastern Region, land is viewed as more valuable for the sand underneath the topsoil. Sand-weaners actively destroyed the topsoil layer for concrete production. So, the farmers are the ones who are protecting that topsoil because the production of food staples is providing a protective barrier for any use of the land in the future.

Farmers, perhaps unknowingly, are at the forefront of climate mitigation.

Where the sand has been mined the soil can no longer support tree growth creating pockets that are hotter in Harmattan. The ground temperatures are becoming hotter and dangerous. While it may not seem important, polyculture farmers are planting trees that serve as protective cover for the cocoa trees and are also a major protective factor against climate change in the region. It’s interesting to see how farmers, although they are not seen as major advocates for climate mitigation, are the ones at the forefront of it but not being paid or recognised for it. The average “Cocoa farmers earn a per capita daily income of approximately USD $0.40-$0.45 on cocoa. This amounts to an annual net income of USD $983.12-$2627.81 and accounts for two thirds of cocoa farmers’ household income”.

What do you find most challenging about your work?

The inequalities. I have the immense privilege of having the time to devote to reading this incredible archival material and the financial support to do it. The majority of documents are found in Europe. For example, The Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana’s library houses only a few primary documents. The librarian explained how it’s a very underfunded area of the institute because most of the funds go towards scientific research to make cocoa production resilient. I then went to the University of Birmingham and there’s a special collection there called the Cadbury Papers and there were boxes upon boxes upon boxes of information. There’s a wealth of information but at the same time it’s extremely inaccessible. Even the person I was staying with in Ghana, when she needed a map to protect some of the lands in a legal case, the Research Institute wouldn’t give her access to the material. As an international researcher, I was the only one able to get access to that document. In the other parts of my work, I found that the people who are on the front line living the work, don’t necessarily even have the chance to talk to a legal firm and ask for support. It took me, someone who had studied in elite institutions, to connect the community to what it wanted and needed. I find it very hard to be significantly more privileged than the people with whom I work. It makes me question why academia has that power in the first place.

What do you enjoy about being at Queen’s?

I love the dinners at Queen’s. It’s fun engaging with people you wouldn’t usually meet. The College is a cool entrance point to conversations I wouldn’t normally have. Last night on one side of me I spoke to someone studying the intersection of American History and Indigenous history and how indigenous governance systems impacted the constitution. And the person next to her was studying soil bioacoustics for conservation. At the core, we shared a lot of our research, but I would never have imagined that until the conversation happened. On top of this, there’s amazing food and I think you have the best conversations about anything over a good meal. Food is so fundamental to how humanity interacts with one another.

What’s your favourite place in Oxford?

I love my daily walk through Port Meadow into town. It’s just one of those Oxford spots that people remember with a smile. It’s very peaceful and even on a January day when there’s no sun, there’s a serene fog and you can imagine being in Pride and Prejudice. The walking here is my favourite part of the city; there are hidden passageways and footpaths that you just don’t get in America.

Can you recommend a book?

There are Rivers in the Sky by Elif Shafak. This is such an interesting story that explores the Turkish water crisis through fiction over different times and place. It’s a great book that I didn’t know I needed to read.