Felix Taylor, Library Assistant

George Augustus Simcox was a classical scholar, a poet, and Librarian and Fellow of the Queen’s College, elected in 1863 at the age of twenty-two. Years later, his name was in all the newspapers: ‘MR. SIMCOX’S DISAPPEARANCE’, ran the headline in the Manchester Guardian in 1906.[1] Simcox had been reported missing along the coast of Northern Ireland, where he had left his hotel to walk near the Giant’s Causeway and failed to return. His habit of reading while walking, his ‘rambling gait’, and his advanced age made it likely that he had fallen from the cliffs. ‘Dr. M’Grath [sic], Provost of Queen’s, his executor, said the College authorities and his bankers had heard nothing from him since’.[2] Having been presumed dead following weeks of searching, part of his extensive library was given by Magrath to Queen’s. 120 years on, it reveals Simcox’s deep interest in theology, Latin literature, and contemporary romantic poetry.

Born in Kidderminster, Simcox came from a literary family. He was the eldest brother of William Henry and Edith, both distinguished in their own fields. Edith is now best known for her friendship with George Eliot, but her study of early civilizations and involvement in the trade union movement meant that she was a respected intellectual and social reformer. William Henry was a theological scholar, also at Queen’s, and went on to write the first full-length biography of Barnabe Barnes, patron of William Shakespeare. During the 1870s and 80s, all three siblings were writing for some of the foremost literary periodicals of the day, including The Academy (whose editor was a Fellow at St John’s) and The Fortnightly Review.[3]

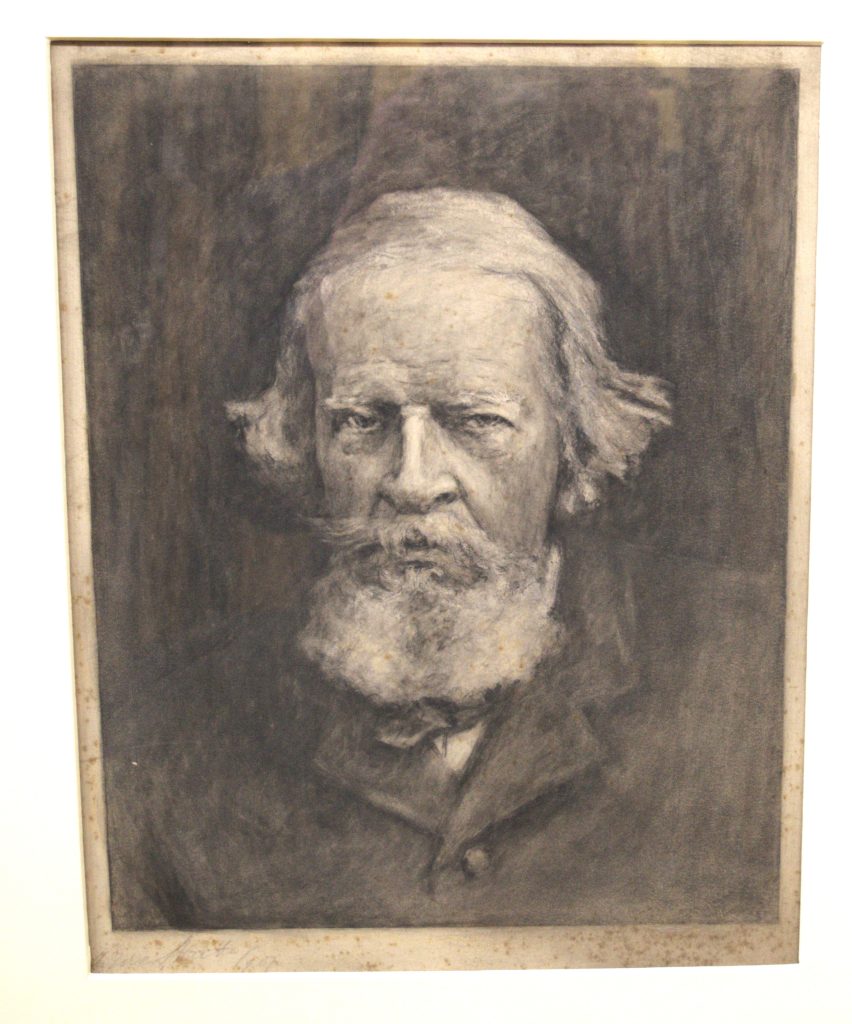

During his time as an undergraduate at Corpus Christi, Simcox was celebrated for his sharp mind and quick wit. ‘No name was better known in the Oxford of forty years ago than that of G. A. Simcox. He was regarded as the ablest man of his year. Tall, spare, and somewhat stooping … he struck you at once as a remarkable personality. But his oddity was also unmistakable’.[4] After being elected to Queen’s, Simcox began to appear as an unconventional donnish figure, mild-mannered yet eager to contribute in any way that he could to literary society. Simcox’s absent-minded presence at the university is immortalised in Oxford Sketches, a set of caricatures by illustrator Sydney Prior Hall, as a ‘drooping figure with trailing gown … strolling outside of Queen’s College and gazing upon various pebbles, straws, and trifles that lay on the pavement’.[5] These contrasting portraits of Simcox as both a keen academic, once president of the Union, and a whimsical eccentric suggest a marked change in character; it may be that the Fellowship allowed his ‘oddity’ to deepen; perhaps also his developing interest in contemporary poetry was considered unusual by other scholars.

The Assyriologist A. H. Sayce remembers Simcox introducing him to the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, who was a guest at one of Simcox’s college lunches. Swinburne, then admired in Oxford for his early collections of taboo-breaking verse on pagan themes and same-sex love, had apparently been ‘making himself sick on a surfeit of sweetmeats’ and was unable to eat the lunch Simcox had provided.[6] Certainly Simcox would also have known Walter Pater – Queensman and burgeoning literary critic whose Studies in the Renaissance helped kickstart the aesthetic and decadent movements – and may also have been involved in the founding of the Savile Club, which he joined in 1877.[7] If his library is anything to go by, he may also have known or corresponded with William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti – both of whom worked on the murals of the Oxford Union where Simcox was later president.

Simcox was himself a poet, though unappreciated by his peers. Prometheus Unbound: A Tragedy was published in 1867, a retelling of the classical myth in line with Shelley’s interpretation, begun during his first winter at Queen’s. This was followed two years later by Poems and Romances. The collection reflects the influence of Swinburne, Morris, and Rossetti, particularly the Arthurian poems ‘The Farewell of Ganore’ and ‘Gawain and the Lady of Avalon’. Simcox also admired Lord Bulwer-Lytton’s King Arthur (1851), which was part of his library. He continued to publish individual poems in The Cornhill Magazine and Good Words into the 1870s, but his enthusiasm for composing verse seems to have waned. ‘He was discouraged by the unpopularity of his books, and publishers were shy of them’, noted his friend, W. Robertson Nicoll.[8] Even before the release of Prometheus Unbound, he was doubtful about its success and warned readers of this in the preface: ‘A poem after the antique is likely to be a failure, and such failures are mischievous, because they lead us to exaggerate the difficulty of entering into a literature greater than our own’.[9] He was proud enough of Poems and Romances, however, to get at least one copy bound in expensive enamel covers. While at Oxford he wrote a two-volume History of Latin Literature, which he hoped would make his name, although it ultimately failed to sell. ‘It is to be feared,’ noted the author of his obituary in the Manchester Guardian, ‘that Simcox had developed too strongly the old academic habit of perpetual accumulation, frequent schemes of writing, and constant postponement of the pains and perils of authorship’.[10]

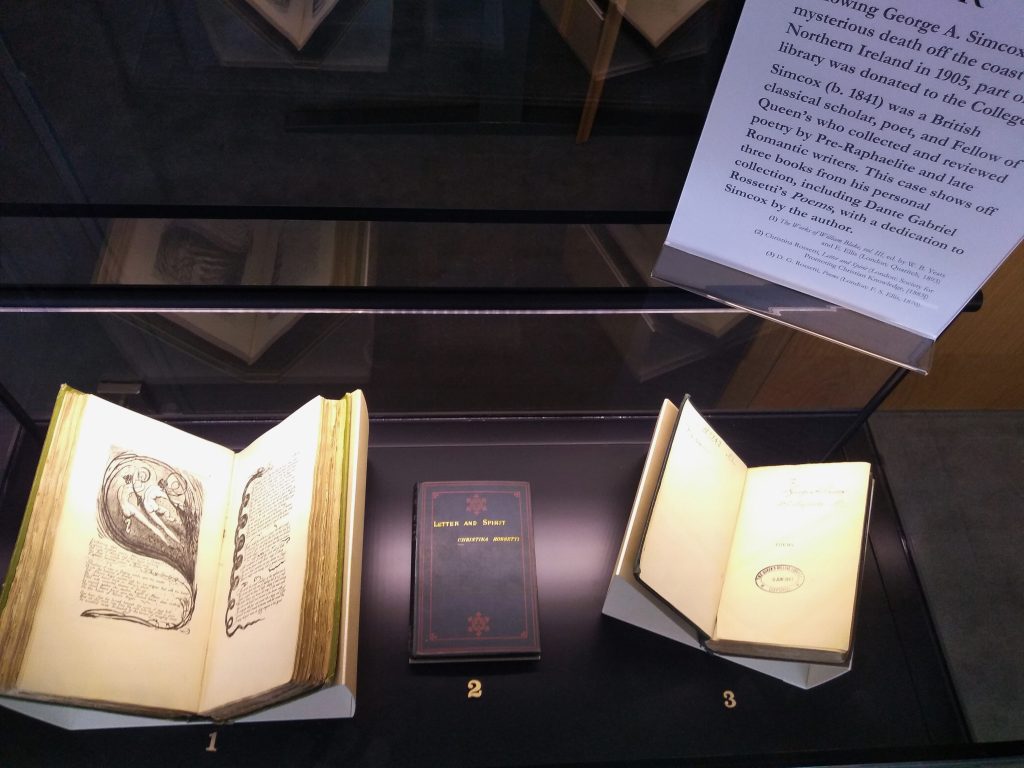

The three books on display in the New Library exhibition case testify to Simcox’s interest in romantic poetry. His first printing of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Poems (1870) is signed ‘From the Author’, suggesting that Simcox may have corresponded with the Pre-Raphaelite at one time or another. Famously, Poems contains ‘The House of Life’, the intimate sonnet sequence buried with Rossetti’s wife Elizabeth Siddal in 1862 and then retrieved after Rossetti had her coffin disinterred seven years later. Next to this is a volume of poetry by Christina Rossetti, one of several of her books owned, and presumably reviewed, by Simcox. Finally, his library contains a resplendent copy of The Works of William Blake: Poetic, Symbolic, and Critical, edited by the poets W. B. Yeats and Edwin Ellis in the early 1890s, and containing lithographs of Blake’s prints. This three-volume set was limited to 500 copies – further evidence that Simcox maintained an appreciation for art and literature throughout his varied life, mysteriously cut short.

[1] ‘Mr. Simcox’s Disappearance’, The Manchester Guardian (17th July, 1906), p. 14.

[2] Ibid.

[3] W. Robertson Nicoll, A Bookman’s Letters (England: Hodder & Stoughton, 1913), p. 107.

[4] ‘George Augustus Simcox [obituary]’, The Manchester Guardian (21st July, 1906), p. 8.

[5] ‘George Augustus Simcox’.

[6] A. H. Sayce, Reminiscences (London: Macmillan, 1923), p. 39.

[7] Savile Club, The Savile Club, 1868 to 1923 (England: privately printed, 1923), p. 113.

[8] Nicoll, p. 106.

[9] G. A. Simcox, Prometheus Unbound: A Tragedy (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1867), vii.

[10] ‘George Augustus Simcox’.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)