Anne Beaumanoir is but one of her names.

She exists, indeed she does, not only in

these pages, but also, to be precise, in Dieulefit,

a village – ‘God-made-it’ – in south-eastern France.

She does not believe in God, but He no doubt believes in her.

And if He does exist, then surely He made Anne.

Anne Beaumanoir ist einer ihrer Namen.

Es gibt sie, ja, es gibt sie auch woanders als auf

diesen Seiten, und zwar in Dieulefit, auf Deutsch

Gott-hats-gemacht, im Süden Frankreichs.

Sie glaubt nicht an Gott, aber er an sie.

Falls es ihn gibt, so hat er sie gemacht.

Anne Beaumanoir : c’est un des noms qu’elle a.

Et elle existe, oui, elle existe bel et bien et donc

ailleurs que dans ces pages, précisément à

Dieulefit, une petite ville dans la Drôme.

Elle ne croit pas en Dieu. Qu’Il croie en elle

n’est pas exclu. Si Lui existe aussi, il est probable qu’Il la fit.

With these opening lines, Annette, the protagonist of Anne Weber’s award-winning modern epic is brought to life. Indeed, one might say, the heroine is born three times over: First in German, the author’s mother tongue, then in French, the language which Weber adopted after having settled in Paris as a young adult, enabling her to translate her own writings and produce a consistently bilingual literary oeuvre. Having been published in 2020 as Annette, ein Heldinnenepos (Matthes & Seitz)and Annette, une épopée (Seuil), the work, finally, made its way into English and appeared once again as Epic Annette: A Heroine’s Tale (Indigo Press, 2022), in Tess Lewis’s translation. What the work’s very first lines also make clear, however, is that Annette’s existence is more than literary. Weber’s account is based on the biography of a real, historical figure – the French Resistance fighter and anti-colonial activist Anne “Annette” Beaumanoir, who was born in Brittany in 1923 and died two years after the publication of Weber’s text, on 4 March 2022, in the above-cited village of Dieulefit. As it evolves across multiple languages and contexts of reception, the work continues to question its grasp on Annette’s extraordinary story and the epoch-defining historical events which it traverses, therefore grappling with the uniquely fraught relationship between literary representation and historical testimony.

On 8 and 9 February 2024, I had the pleasure of discussing these topics with Anne Weber and Tess Lewis when hosting them for two events in Oxford. This initiative developed out of my doctoral research, which explores transnational forms of memory in contemporary French and German literature, and was made possible thanks to the expertise and generous support of the Queen’s College Translation Exchange (QTE), the Oxford Comparative Criticism and Translation Research Centre (OCCT), the Medieval and Modern Languages Faculty (MML), and Karen Leeder, the Schwarz-Taylor Chair of German.

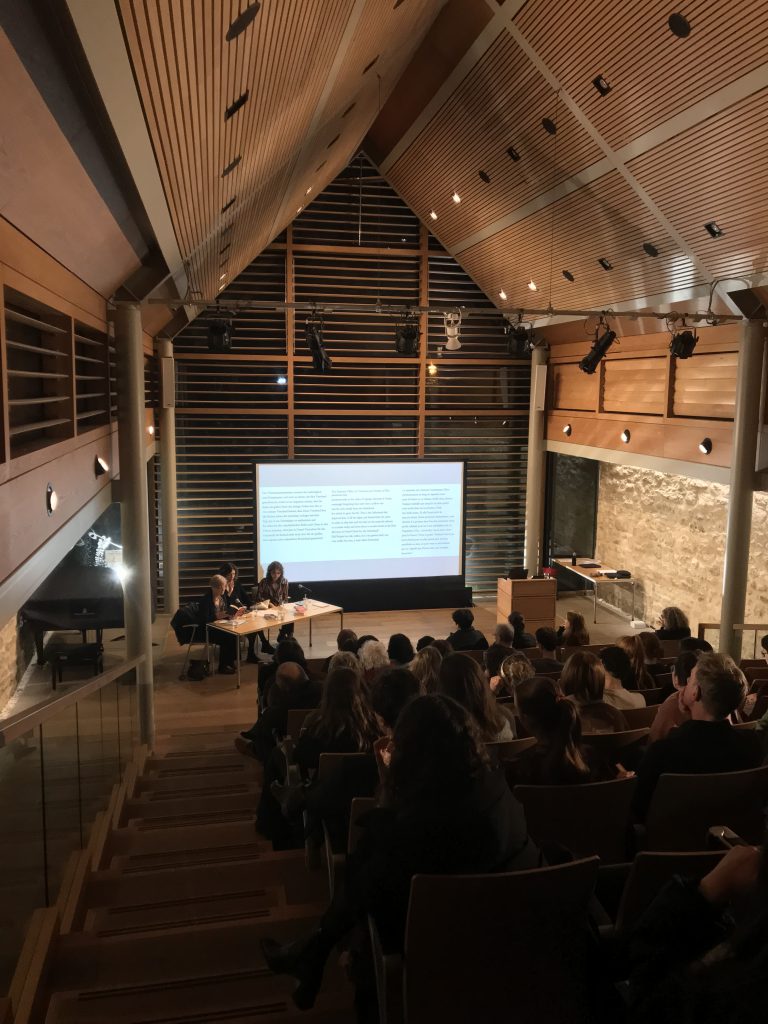

During the first of the two events, a podium discussion held in the Shulman Auditorium at Queen’s College 8 February, we explored how the text’s existence across different languages mediates its relationship to history. On the one hand, the author’s sympathy for Annette and emotional investment in her story became palpable; yet, Weber simultaneously highlighted distances which separate the first-hand experience of history and any narrative account completed with the benefit of hindsight. Beaumanoir was confronted with life-and-death decisions at a very young age, facing historical situations as they unfolded. During her engagement for the Communist resistance against the German Occupation of France, she thus decided, at great personal risk and against her superiors’ orders, to save three Jewish children from being arrested by the Gestapo. After the end of the war, she sided with the Algerian Independence movement in its struggle against French colonial oppression – a new form of resistance, which eventually saw her incarcerated and forced into exile in North Africa. Obliged to reduce the multi-layered complexity of this life to fit the parameters of a singular narration, Weber emphasised that her work does not lay claim to any absolutist notions of historical truth. Instead, she seeks to retain an awareness that her relationship to Annette’s story is inescapably marked by her own subjective vantage point – especially given that she approaches it as a German author, whose family history is burdened by her ancestors’ complicity in extreme German nationalism and National Socialism.

In completing two versions of the heroine’s tale in French and German, Weber also had to reckon with fundamentally different audience expectations, often adding sections which explain French cultural and historical references to her German public – and vice versa. In some cases, however, the differences resulting from Weber’s self-translation are more than just points of information and instead affect the very core of a given section’s rhetorical thrust. The death and burial of Roland, Annette’s lover, and a fellow Resistance fighter, exemplifies this: Refuting the epithet Mort pour la France, which the government places on his grave, the narrator highlights the violence which the Jewish Roland experienced at the hands of the French Vichy administration, which eagerly collaborated with the Germans. In German, Roland is then said to have died not for the ‘Vaterland’ [fatherland] but for a different ‘Bruderland’ [brotherland]; in French and in Lewis’s English version, by contrast, he is said to have died for a land called ‘fraternité’ – for ‘fraternity’. Explaining this difference, Weber noted that ‘fraternité’ is one of the core ideals of French republicanism, which is held up against the moral corruption of France under Vichy. In using ‘Vaterland’ and ‘Bruderland’ in the German version, by contrast, Weber obliquely critiques her own country’s history, given that for German readers, the former term immediately evokes its abuse by the Nazis, whereas ‘Bruderland’ provides a more positive, resistant variation on the same family metaphor.

Lewis outlined that, when rendering the work in English, she experienced the differences resulting from Weber’s free self-translation as a kind of liberation, which enabled her to select the version she deemed most effective for an English-speaking audience. She was also able to build on the work of cultural mediation which Weber had already begun, often combining the historical information the author added for French and German readers respectively into a version which offered sufficient background for an English-speaking audience. The biggest challenge for Weber and Lewis alike, however, they both stressed, was conveying the text’s unique rhythm and free verse form across different languages, and exploring anew what a modern epic mode might mean with each new rendition in German, French, and English.

During our second event with Weber and Lewis, an interactive translation workshop held at St. Anne’s College on Friday, 9 February, we were able to gain first-hand insights into this very process. Moderated by Charlotte Ryland of QTE, the workshop brought together diverse participants from first-year undergraduate students to professional translators. Working together in mixed groups combining French and German speakers, they engaged with selected passages from both original versions in order to produce their own, collaborative English-language rendition. Practising what Lewis termed ‘translation as triangulation’, participants presented their results at the end of the session, compared them to the published Epic Annette, and discussed their challenges and choices with both the author and the translator. This conversation once again highlighted the complexity of Lewis’s task – doing justice to a formally unique and already-manifold, border-crossing original –, and ultimately valorised the work of translation as a continuation of the creative processes and mediation efforts at stake in all literary writing.

It was deeply motivating to learn from Weber and Lewis during the two days of their visit to Oxford. The generous and thoughtful insights they gave into their work on ‘the rhythm of a life’ – as Lewis’s translator’s note puts it – confirmed my belief in the value of translating, both in a literal and in a metaphorical sense, between different experiences of history and across the boundaries of existing communities of memory. Annette’s moving story, therefore, can ultimately provide an encouragement to question established historiographies find new, dynamic articulations for our evolving relationship with the past, which shapes our ethical consciousness and therefore, is bound to affect both our present and our future.

Hannah Scheithauer is a DPhil candidate in French and German at The Queen’s College, and is currently a Guest Doctoral Researcher, Friedrich-Schlegel-Graduiertenschule, FU Berlin.

Header photo: Translation Workshop with Charlotte Ryland, Tess Lewis, Anne Weber, and Hannah Scheithauer (left to right).