Dr Matthew Shaw, Librarian

If you don’t like something, particularly something being read, you can always chuck a stool at it. This, at least according to a near-contemporary satire, is what Jenny Geddes, a vegetable seller, did in 1637 upon hearing the dean of St Giles in Edinburgh reading from a new book. While the details of what happened are uncertain, there is no doubt that a riot in St Giles was started by women as a protest against Charles I’s imposition of Archbishop Laud’s Scottish Booke of Common Prayer – popularly known as ‘Laud’s Liturgy’ – on the Church of Scotland. In so doing, they precipitated the outbreak of the movement that became known as the Covenanters and the path to civil war in both kingdoms.

The preface from the King informs its readers and listeners that the work was drawn up with Scotland explicitly in mind, ‘as we had reason to think would best comply with the minds and dispositions of our subjects of that kingdom’. These changes included substituting the word ‘Presbyter’ for ‘Priest’ in the rubrics, and adopting the Scottish usage of ‘Yule’ for Christmas and ‘Pasch’ for Easter. However, the text was imposed without proper consultation, and by attempting a compromise between puritan and catholic sensibilities it pleased no-one. The text was based on the new 1611 Authorized (King James) translation of the Bible, requested by puritan divines at the Hampton Court conference of 1604, but this was outweighed by the liturgy for Holy Communion (the new text referred to the ‘Holy Table’, as opposed to ‘Table’, meaning that Communion could not take place around a common table in the body of the Church, but was received at the altar, and the Prayer of Consecration explicitly consecrated the elements as ‘body and blood’). The Litany, versicles and responses, to which Presbyterians objected, remained. The Prayer Book introduced more Saints’ Days than were to be found in England. All this was enough to cause those with more puritan views to reach for their seats as handy projectiles.

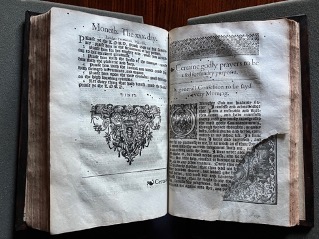

1 Certaine godly prayers, with torn corner. Note catchword ‘certaine’ on the left hand side, which is often in evidence in copies with the Godly Prayers removed.

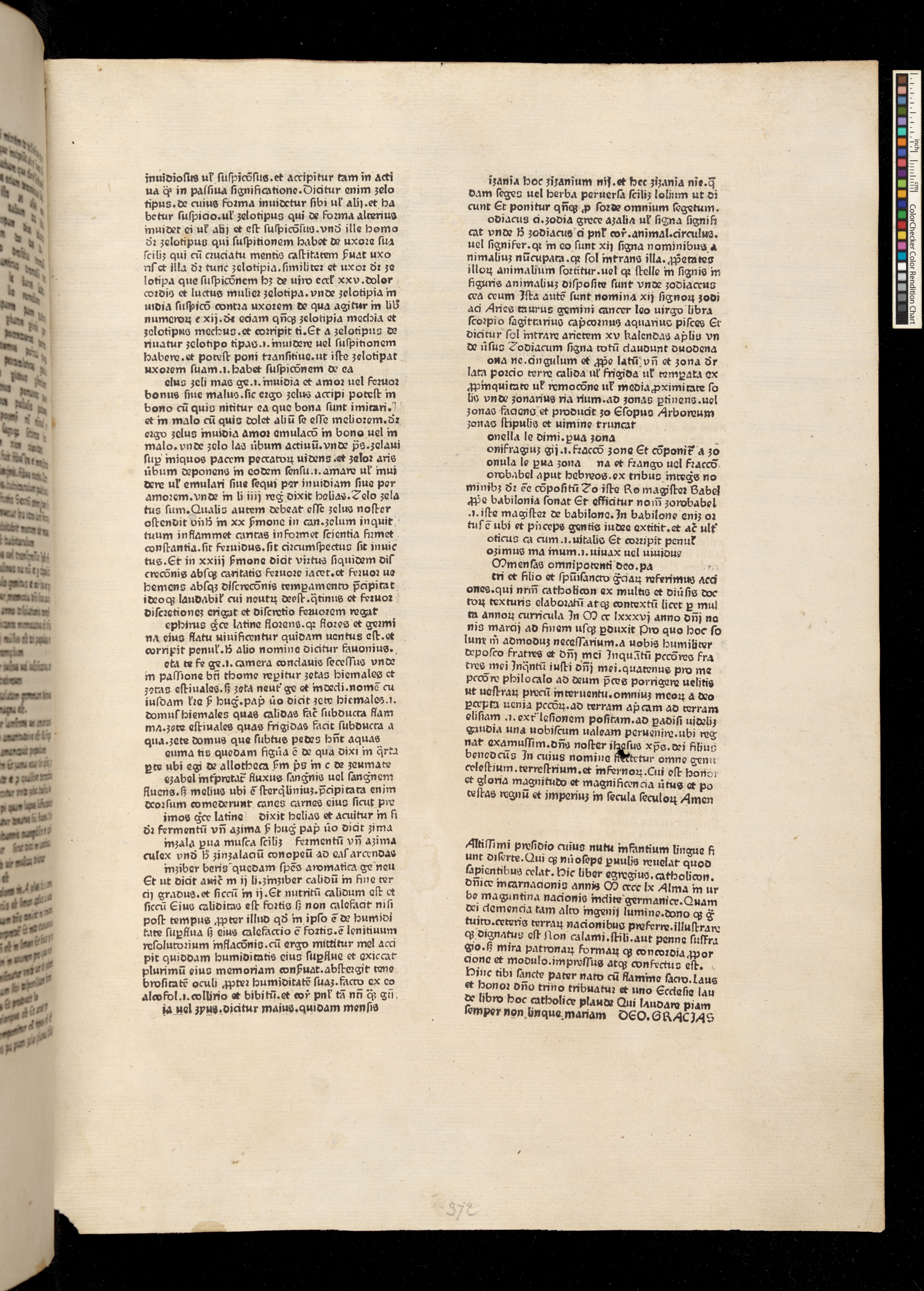

As such, copies are scarce. The English Short Title Catalogue now lists 64 copies (including the one in the College Library), and perhaps around 100 survive in total. It was not reprinted or reissued, although the Prayer Book did form the basis for the Communion Office of the Episcopal Church in Scotland, from which the Protestant Episcopal Church in America is derived. The Upper Library holds two copies, one owned by Provost Thomas Barlow, and the other pictured above (shelfmark 80.b.14). It is a handsome object that has survived remarkably well, despite some evidence of hungry bookworms. The text is printed in blackletters, with rubric in Roman and italic typefaces. The title page is printed in red and black ink, and decorated capital letters throughout emphasise the book’s Scottishness: a ship flies St Andrew’s Flag of Scotland, and thistles decorate other corners. The binding is blind tooled, and has marks that show where the chain was attached to keep it safely in the Upper Library.

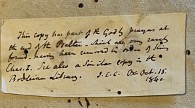

2 Manuscript note tipped into the book, highlighting the rarity of this edition

The volume also contains a pasted-in note dating from 1840: ‘This copy has part of the Godly prayers at the end of the Psalter, which are very rarely found, having been removed by order of King Chas. I.’ The prayers are indeed present at the end of the Psalter, and before the collections of psalms, although the right-hand corners are torn. It is uncertain why the prayers were ordered to be removed, and it seems plausible that the decision was more that of Laud than Charles, but the consequences were the same.[1] The text can now be seen in the British Library, in Edinburgh, in the Bodleian – and in the Upper Library. Intriguingly, the suppressed sheets may have been disseminated separately: a few fragments and complete sheets can be seen in Edinburgh.

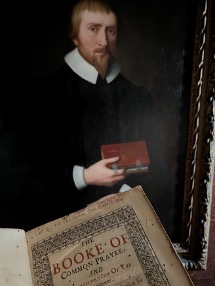

Why is this controversial (and rarely found complete) book here? The answer lies with Provost Christopher Potter (1591-1656), whose portrait can be seen in the Magrath Room. A noted disciplinarian, Potter allied himself with Archbishop Laud and also served as chaplain-in-ordinary to Charles I. Is it impossible to imagine him, at Laud’s or even Charles’ instruction, tearing the corners of the pages of the Godly Prayers, before donating the book to the College?

3 Portrait of Christopher Potter and the Booke of Common Prayer, 1637

[1] G. Donaldson, Making of the Scottish Prayer Book of 1637 (Edinburgh, 1954).

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)